《巴顿·芬克》经典观后感10篇

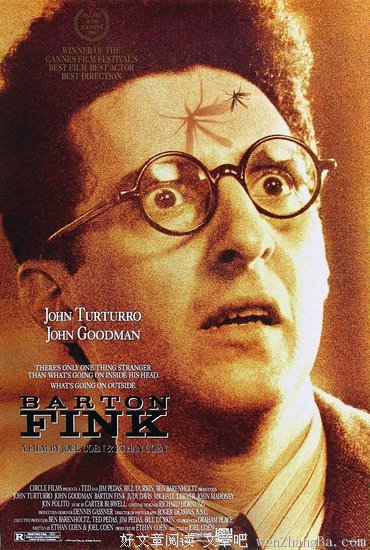

《巴顿·芬克》是一部由乔尔·科恩 / 伊桑·科恩执导,约翰·特托罗 / 约翰·古德曼 / 朱迪·戴维斯主演的一部剧情 / 悬疑 / 惊悚类型的电影,文章吧小编精心整理的一些观众的观后感,希望对大家能有帮助。

《巴顿·芬克》观后感(一):Barton Fink

A man moves from New York to Hollywood hoping to make it as a film writer, Barton Fink as a whole is a satire to the notion of artistic creations. While writers in the story like Fink and Mayhew claims themselves to be artists and understanding of the struggles and glories of the everyday people, it is satisfying to watch how little they actually understand these concepts. With the paper thin walls of the hotel, it is perhaps not surprising for characters like Charlie to be enraged by their feigned sincerity, and for their abrupt and forced intrusion into their lives. Ultimately it is not this understanding that sells in the box office, but a much simpler method that could be achieved only by everyday people. What Barton Fink experienced was not a writer's block, but the inability to construct a simple story which his complex mind could not conjure. A beautiful premise behind a gorgeous film, but the film overall is really hard to fully apprehend as I am still left puzzled by several motifs and symbols.《巴顿·芬克》观后感(二):巴顿-芬克:创作与分裂

这部电影是属于那种绝对晦涩,难以理解的片子,而且极具开放性和话题性,一百个人眼中可能有一百种完全不同的“巴顿•芬克”。对于这种影片,你可能会难以下咽,或者看完后便弃之不理,我想大部分普通观众都是如此;你也可能在观影完毕之后,带着一点点好奇心,去读一些影评,尝试理解,甚至简单的发表一些自己的见解,这是电影爱好者会做的事;而剩下一些人,则会努力去提炼一种观点,然后试着用逻辑去论证,这可不是闲着没事儿干,会这样做的人有两种,一种是专业影评人,另一种则是电影发烧友。而我今天这么干了,所以有必要声明一下:我属于后者。处女长评,有见笑的地方请多多包涵。

一、剧本创作

首先,这是一个有关创作的故事。创作,是一件及其严肃的事,带有很强烈的个人属性,是一种对自我和外界的理解和表达。而我们的主角——巴顿•芬克,就是这样一位有着执着追求的创作者:不甘庸俗,视角独特,渴望开创新的形式,获得real success。不出意外的,拥有此番雄心壮志的巴顿,被请到好莱坞,试水“庸俗”,看似讽刺,却很现实。

电影进行到此时,依然是相对正常的。当不再享受创作自由时,压力随之而来。巴顿的性格软肋开始显现,软弱、偏激、焦虑,而对于这些感觉的呈现却是影片的最大亮点之一。科恩兄弟对精神的描写和氛围营造令人赞叹不已,每一处细微的声音,呼吸和风声都清晰可辨,镜头的移动和凝滞感,简单却很有穿透力的配乐,让画面的空间纵深感很强,空洞诡异,令人不寒而栗。

而此时巴顿的心境也莫过于此。仅仅由于灵感的缺乏导致剧本无法进行,便如此焦虑甚至接近崩溃边缘,这只是针对于巴顿•芬克的状态,毕竟不是每一位创作者都能像导演科恩兄弟那样拥有足够独立自由的创作环境。这样一进一出进行对比,可以看出电影并非是带有自传性的,科恩兄弟站在同业者的角度进行审视和讽刺,当巴顿芬克在狂欢的人群中近乎癫狂的吼出那句:I am a creator!我们对他却是可笑可悲又可敬。同样对于在艺术和商业间挣扎的创作,也是如此。

二、旅馆

破败却规整的旅馆,承担了影片中大部分场景。古旧的家具,斑驳的墙壁,阴暗封闭的空间,周全却又神秘的服务员,说不尽的诡异。实话讲,这本身就是一个很适合开发异世界的场所,而影片后来的进展也证实了这一点。

电影始终是紧紧围绕主角巴顿•芬克展开的,而巴顿对于这所旅馆的感觉,其实正是导演所要呈现给观众的感觉,而且这种幽闭空间也最适合导演来施展。就如上一节里提到的,本片神乎其神的空间感和氛围营造,正是得益于这个旅馆,以及科恩兄弟对于电影超强的掌控力。

谈到旅馆,就不得不提巴顿热情好客的邻居——查理,这个看似健谈体贴的胖子。得益于旅馆墙壁良好的透音效果,巴顿总是能第一时间判断周围邻居的行动,比如接打电话,邻居的走位,似笑似哭的怪音,乃至做爱性虐的声音,无不清晰可辨,正是在这种状况下,他结识了查理。巴顿的性格,注定了他是那种朋友不多的人。所以,当独身居于异乡,遇到一个热情健谈,能给予自己帮助,乃至可以当作倾诉对象的人,巴顿迅速对查理产生了毫无保留的信任。而且,后者身上的特质是巴顿所不具备的。更兼身形上的一胖一瘦,让两者间有了一种微妙的互补。

所以,在巴顿杀人之后,他竟然在第一时间向查理坦白了一切,而查理也绝对可靠的帮助巴顿暂时度过了难关。但是这个看似无比忠诚的朋友,却在两个同样神秘诡异的警察到来后,完全转变了形象:一个身体灼热到可以引燃旅馆的杀人魔王,在烈火中奔跑,射杀警察。此时的查理,是一个可以将内心情绪转化为周身物理变化的人。电影这时也进入了超现实状态,而不仅仅是此前在氛围上隐晦的表现这一点。而接下来查理和巴顿的对话,则更加明确地告诉观众,他本人就是这座旅馆的化身,尤其是查理耳朵里流出的脓水,跟旅馆墙壁上的不明液体如出一辙,再明确不过的暗示。电影此时已经不能用正常逻辑来解释了。

三、杀人

我最喜欢影片中的一处:当巴顿和奥黛丽即将由调情进入正题的时候,镜头从两人身体缓缓地移向了卫生间的面盆,进而深入面盆中间排水管道。这个长镜头不仅加强了空间的纵深感,更是一个精妙绝伦的性暗示。

这里要谈一下巴顿对于女人的态度。多少是由于性格原因,巴顿很少与女人产生情感上的羁绊,虽然他自己解释是因为工作繁忙。但当奥黛丽,这个成熟、知性、睿智的女人,第一次出现在巴顿面前时,他展现了难得的主动。随后的几次见面,可以明显的感觉到巴顿对于比尔的嫉妒,这份嫉妒不仅来自于同行间的竞争,更是由于奥黛丽的存在。好像被压抑了许久,剧本和奥黛丽,在巴顿心中连在了一起。

那为什么奥黛丽会被杀呢?她是被谁杀害的呢?我不知道你们有没有注意这样一个细节:当镜头缓缓进入阴湿的管道,背景音从奥黛丽的呻吟过渡成了查理的狂笑。是的,这个象征性的长镜头不仅是一个性暗示,更是影片的节点。只能有一个解释:在两人做爱的同时(可能正好达到了高潮),查理杀死了在快感中呻吟的奥黛丽。

写到这里,影片中很重要的一部分已经明显了。两点可以被确定:

1:查理是旅馆的化身;

2:查理杀死了奥黛丽。

进而又引申出两个推测:

1:这是超自然事件,查理(旅馆)是独立的存在;

2:巴顿的幻觉,查理是他精神或人格上的另一面。

可能除了导演科恩兄弟,谁都无法做出定论。但联系电影前后,以及影片的超现实表现,推测2的可能性要远远大于推测1。

四、包裹

其实,对于这样一部具有魔幻现实色彩,探寻人性中最灰暗部分的作品来说,非要把剧情讲个清楚明白,是最背离导演立意的。前面对于剧情的分析,只不过是想在这部极其晦涩的电影中,摸索到一些接近于核心的线索。

电影的核心是什么呢?对于本片来说,肯定是最难以捉摸,最不可确定的。我在坚信这一点的同时,却认为这个核心已经在影片中具象化了:查理留给巴顿的包裹。

这篇影评的标题是:创作与分裂。那么巴顿分裂了吗?答案是肯定的。且不说查理很大可能上是巴顿的二重人格。在经历一番风浪,且得知自己最信任的朋友是杀人狂,巴顿却看着查理留下来的包裹,重新回归了平静,并进入到一个才思泉涌的阶段。

包裹,是巴顿自己的。

——里面装着奥黛丽人头。我相信很多人的第一感觉是这样的,包括我自己。但这种顺理成章的推断,你即不能否定,更不能当作已定事实。毕竟影片本身就处在一个不断变化的,现实和想象之间的一个灰色区域。

从巴顿第一次踏入旅馆,就开始盯着墙上一副沙滩美女画作,在诡异中听到了大海的浪涛声。巴顿此时身处在外界压力中,踏上一条不可确定的道路,结果可能是获得梦寐以求的成功,也可能是背离自己本意的虚行,渴望却害怕。电影通过一副画作展现出一种类似的感受,一种象征性的心境。而巴顿大部分时间都是被这两种感觉交织侵袭,随后发生的各种颠覆事件,更是将巴顿推向了崩溃的边缘,直至包裹的回归。

前后的变化是如此突兀,却又很符合本片的超现实气质。包裹象征着巴顿遗失的某一部分,从到达旅馆的那一刻就不见的,有关本性的东西。但作为一个物件,它又是简陋且笨重的,所以我们后来看到无论走到哪里,巴顿都会拎着一个极别扭的包裹,似乎是不可离身的物件。在影片结尾,带着包裹的巴顿•芬克,终于见到了曾在画中渴望的场景:沙滩上听海的美女。

这是很奇怪却又很具有特质的表达,我相信:包裹里的东西,就是巴顿•芬克本身。

ps:以上纯属个人观点。不喜勿喷,可以来找我辩的

《巴顿·芬克》观后感(三):公民巴顿·芬克

巴顿芬克,一位来自纽约的剧作家,来到了西海岸的洛杉矶。在短短几天时间里经历了绝望与消沉,因为一个偶然事件起重要作用,罪恶吞噬良知,人性的剥开了自己的丑恶,究竟发生了什么让他迷失了自我,让他逃离了好莱坞?让我们来看看他们的回答。

伽兰:我最近一次见到他是在他编写的话剧在纽约公演大获成功的时候。没错是我叫他去的好莱坞,在我看来去那里未尝不是一种可能,那里有的是cash。只要你努力了适应了你的人生就会上一个新的台阶,即使不适应回来就好。纽约依旧欢迎你。

利普尼克:当我第一次见到巴顿芬克的时候他自己表现的是那样的拘谨那样的不适应,但在我看来,我,做为好莱坞的投资人,一位商人,这是完全可以理解的。我完全可以肯定他的才华,他在纽约可以是个出色的编剧,在这里也可以。我的想法很简单,一部有关于摔跤手的B级片,这很难吗?这不难,这么说吧我都替他想好了开头:一位在下东城的小伙子,为了生计去摔跤。可是,我们可爱可敬的巴顿先生,竟然写了一个如此糟糕的剧作,还口口声声说这是最好的一部。亏我还亲吻过他的脚掌,训斥了自己的手下,他一点都对不起每周两千美元的报酬!

奥黛丽:血!血!血!为什么我的身上会有这么多血,我难道死了吗?不,不要这样。是谁杀死了我?巴顿?还是我的老板?是可怜的巴顿求我来给他建议,我才来的旅馆,在我看来写剧本其实不难,至少从我帮老板代笔之后他的声誉反而更高了。可我后悔告诉了巴顿,在他眼里我的老板虽然品行不好,但至少是个好作家,至少可以让他相信好莱坞。都怪我让他知道了真相,我知道他从偶像身上看到明天,好莱坞黑洞,抽干压尽创作者的才华。但真正打击的是我。是我!我不想为了什么魔幻现实主义,什么存在主义就让我死去,我也不想要悬念,我只希望能够再次回到我的老板身边。

查理:在我看来人生是悲凉的,生命是荒诞的毫无意义的在这之后我需要做的就是通过暴力让彼此之间发生微妙的化学反应,糜烂,对!糜烂就会产生新的价值。其实我很不喜欢巴顿口口声声说着关心百姓,只关心自己的名声,不懂得去总是夸夸其谈,不仅好大喜功而且脱离脱离实际内心脆弱。他自以为充分掌握了解这个世界,在我看来他只是想借底层人物来表现自己知识的精英立场。当我在大火中血战的时候,他能做的只是遁身而逃,是我拯救了他!似乎他墙上那张沙滩美女图才是他真正向往的地方。

沙滩美女图:我是一张贴在腐烂的透漏着粘液的壁纸上的一张画,我看到了一切,我也知道巴顿喜欢的其实是像我这样的生活。我想巴顿见我的第一眼就对我留下了深刻的印象,因为我完全与这个虽然有着热带气息但陈旧的鬼气森森的地方不一样。我看到的他是一个纽约客,看到了他绞尽脑汁却只打了短短几行字的剧本却因为奥黛丽的死而灵光乍现一口气写完。听到了他和连环杀手查理的对话,也看到了他所拥有的对圣经的信仰。我不能告诉你究竟是谁杀死了奥黛丽,但我想说看着他在那之后脆弱的坐在于是的样子,我真不忍心。或许他不应该来好莱坞,好莱坞的商业好莱坞的气息对他这种小知识分子来说太不适合了。他就应该像伍迪·艾伦一样,在纽约去搞艺术电影。

最终巴顿·芬克离开了好莱坞,或许他去了纽约或许他去了他向往的地方。

《巴顿·芬克》观后感(四):如果你们不给我解释梦,我就把你们的营帐变成公厕!

这部电影是以作家巴顿·芬克为主线,脑中的本我查理为暗线进行交叉叙事的电影,讲的是芬克本人在写作当中的自我意识与外界声音的争斗,将潜意识世界与真实世界在封闭的旅馆空间中交织在一起。但是芬克和查理分别由两位体貌差异巨大的演员扮演,会让人觉得他们是完全不同的两个人,即便这样理解,整部电影也是完整的,这就是这部电影比较精妙的地方,可以有非常多种解读。巴顿芬克的剧本在百老汇得到好评,他的作品以平民视角为主,他本人也认为戏剧应该属于大众而不是贵族阶层。好友建议他去好莱坞闯一闯,芬克决定去试试,但是他心里也很害怕商业化的好莱坞会背离他写作的初衷。

芬克跟好莱坞公司老板碰头,老板对电影一窍不通,但他希望芬克写一个摔跤手的剧本。他说好友看过他的百老汇戏,很好看但是有点娘,他希望芬克写一部男子汉的摔跤电影(就是好莱坞式的,没有情节的肌肉男打斗戏)。

《巴顿·芬克》观后感(五):《巴顿芬克》:晦涩难懂的超现实电影

看完这部电影,我其实完全无从下手,难以明白其中的含义。但我又想写下影评,表达下对这类“超现实”电影的感觉。看过《穆赫兰道》后,我本来以为很难再有这样晦涩难懂的,超现实,人和心魔的斗争,现实和梦境,想象的交汇的电影。但《巴顿芬克》却比《穆赫兰道》更加晦涩难懂,人格分裂在这部电影似乎存在,又似乎不存在,一些超现实,超自然的现象,似乎是真实存在,又似乎是不存在的。见过一个人对这部电影的评价很对,大意如此:在这部逻辑不能解释的电影,只能从精神层面对其进行剖析了。港片也有这类型的电影,杜琪峰的《神探》,便是把超现实和人的想象事物结合起来,但做到十分通俗易懂,也让现阶段的我更加容易接受。像《巴顿芬克》,《穆赫兰道》的,可能我需要再看更多的电影才能理解他的含义了。

《巴顿·芬克》观后感(六):解密的线索

1·电影本身即是芬克的幻象,一开始话剧演员说的台词,我醒了,从未如此清醒和芬克在后台痴痴的表情是一种对比。芬克想挖掘一个普通人的内心,他藉此发现了普通人生活的真相:价值混乱、困顿、诡异充满离奇荒诞的内容。戏外的芬克创造了戏里的芬克——也正是他自己这个普通人——并由此发觉到了生活中最深层次的黑暗。就像一面镜子,照出了自己是一面镜子,但是镜子里还有镜子……以至无穷无尽的虚无。2·渔夫这个形象为人所忽略但我以为这是最重要的线索,无论是一开始的话剧,还是房间里那张大海的照片、片中至少两次出现过的海浪拍打礁石的画面和最后的那段海边的镜头。这个意向我认为是在暗示戏里芬克的身份——一个渔夫——也是一个普通人。创造者和水手、渔夫之间并没有什么区别。这个意思在船上跳舞那段也有所体现。而渔夫也代表一种对内心宁静的追求,一种心无旁骛的境界。

3·女秘书是缪斯,先是那个比尔的,后来又成了芬克的。缪斯死了,但是留下了头颅——那个盒子。头颅象征智慧,而这个设计象征着缪斯的死去和缪斯的遗留,换句话说,作家写出来的东西都是灵感的尸体——一旦写出来了,就死掉了。拿出来换得别人喝彩的东西不过是一颗头颅。

4·盒子。盒子里是头颅但是为什么不打开?关于盒子有几个细节是有很明显的暗示的。第一个是胖子对芬克说,一个人最重要的东西竟然只是这么一点,只有这么小的一个盒子,这其实是在说作家唯一重要的东西就是那么一点灵感【或者说灵感的尸体】。后面胖子又说,我骗了你,那个盒子不是我的——盒子因此就成了芬克的了。海边的女郎问他,这是你的盒子吗?他说我不知道。女郎问他盒子里有什么?他说,我不知道。这的确合情合理,谁能说清楚灵感这东西到底从哪来又会有些什么呢?芬克在和老板说的时候也交代了,不愿意将故事随便地讲出来——讲出来,故事就成了另一个故事了,灵感也随之死去。再就是芬克拿到盒子之后开始创作自己最重要的一部作品,这也是一个强烈的暗示——他找到了灵感,虽然已经是缪斯女神的一部分了。

5·胖子是谁?胖子是疯子蒙特,也是卖保险的查理,同时我几乎认为他也是芬克的某种化身。他说,我了解那些人的痛苦,所以我干脆替他们结束这一切。而芬克说,好的作品来自于某种痛苦,一种你能感受到的人的痛苦。这不能不说不是一种巧合。如果理解为胖子是芬克的一种走火入魔式的化身,那么从外型、风格上的对比也就可以作为一种佐证。而且胖子和芬克摔跤的部分带有浓重的性暗示,在后面侦探问他是否和胖子有性关系的时候,他说我们都是男的,我只和他摔过跤。按理说这是一个合情理的解释,但是侦探却说,你真是个死变态。为什么?根据后面剧本的内容我们知道芬克写的摔跤是一个人和自己灵魂的摔跤,这是一种比性关系更高层次的精神上的一种碰撞、融合;比起性关系来这是更加深入的层次。而且片中芬克在看样片的时候反复重复着两个镜头:一个是一个胖子吼道我要毁了你;另一个是两个人在不停地角斗。这也是一种暗示,胖子作为他创作中走火入魔的一个化身,带有浓重的毁灭性质,他一开始制造噪音,接着不断打扰芬克的沉思,再有制造命案、纵火、杀人……戏外的芬克一定在创作中找到了自己的一个化身,因为深入感受而充满痛苦、带着毁灭的欲望、不受控制。但是最后这个化身在制造了芬克难以收拾的混乱后走掉了——只留下了一个装着灵感的盒子。一个负责创造,一个负责毁灭,两者源于一体。正如一个卡住的作家在创作时挖出了另一个自己,在制造了各种麻烦后作家有回到了原来的自己,并找到了灵感。

6·墙纸为什么不断地往下掉?也许是因为背后有什么东西被隐藏起来了,有交欢的男女、神秘的杀人犯还有各种各样看不见的事情。

7·蚊子是什么?蚊子,吸血,压榨创作者的才华,害死了缪斯女神,在片中的实体化身是那个神经质的老板,暗指的是好莱坞?也许并不准确,应该是一种缺乏特征的、平庸垃圾的创作环境,一类低俗缺乏敏感无孔不入而又贪婪成性的人。

《巴顿·芬克》观后感(七):才子的向西地狱之行

当影片接近尾声的时候,我们看到巴顿终于把剧本写好交到电影公司老板手中,这是一个关于摔跤手和他的灵魂摔跤的故事,此时相信很多人确信查理不过是一个幻觉,是巴顿的另一面。高安兄弟在这部电影的叙事中没有多少强调情节和人物的虚实感,他把虚实融为一体,不露痕迹,更没有很多关于幻觉的电影最后必定出现令观众恍然大悟的高潮,这也是高安兄弟的叙事特点,从来就避免去营造高潮。《才子梦惊魂》令高安兄弟成为康城影展的宠儿,也令美国的独立电影界震惊,当年一举包揽了金棕榈、最佳导演和最佳男主角。高安兄弟在这部影片里不仅手法高明,角色深刻,而且对好莱坞进行狠狠地讽刺。看过一篇影评说这部影片的灵感与高安兄弟在拍《风云再起时》(Miller's Crossing)有关,当时拍《风云再起时》,高安兄弟一度在编剧的时候写不下去,当时的状态就像巴顿那样紧张、焦虑、恍惚。不知这个传闻有没有被证实,但我还是偏向相信这个花絮的,难道没觉得片中巴顿的饰演者约翰·特托罗戴上帽子的时候跟高安兄弟有点像么?

影片以长镜头开始,从舞台顶端慢慢往下移,我们听到演员在表演时的声音,但镜头渐渐向后拉,终于看到了影片的主角,编剧巴顿芬克。他神情紧张,他是十分在意观众的反应,到谢幕时,这部剧获得全场观众肯定,所有演员希望编剧能一同上台,巴顿依然是那么紧张,其实他是个孤独,永远只活在自己世界里的人,这在接下来的戏中都足以印证这一点。他在剧场的才气被赏识,获得了去好莱坞为电影公司写剧本的机会,但他“一开始是拒绝的。”其实一名在纽约的剧场得到肯定的编剧去好莱坞发展是否真的适合去好莱坞发展令人怀疑,尤其是纽约的剧场界对一味只懂得迎合大众口味的好莱坞不是十分不屑么?不然为何我们看到《飞鸟侠》(birdman)里面那个毒舌剧评人对演好莱坞超级英雄的米高基顿进行无情挖苦。

为了吃饭,也是像巴顿的经纪人说的,你想要你那种意义的成功也要吃饭啊,你帮好莱坞编剧可以令你追求你的成功没有经济压力,巴顿还是接受这份好莱坞编剧工作。在一个海浪拍打岩石的空镜后,巴顿只身一人就来到了好莱坞,入住酒店。从他的剪影出现在酒店的门口,他的孤独我们都是可以感受到的,至于这家酒店则成为了接下来巴顿的创作牢笼。

多次重看巴顿进酒店到入住这一场戏,它令人对这家酒店有种恐惧感。看到一些影评谈到影片的虚实,说酒店也有可能是一个幻觉,但我觉得酒店首先它是实的,其次酒店有着相当耐人寻味的象征意义。它的恐怖感最先是来自它的寂静,它也许像黑色电影里的神秘旅馆,一个住客都看不到,巴顿走进这家酒店的时候,他形单影只,酒店的死静也衬出巴顿的孤独。这家酒店有多静?当巴顿来到前台,按下前台上的响铃,声音在空荡的酒店大堂回响了很久。之后史蒂夫·布西密饰演的酒店店员出现,他是从地下走上来的,这就像一个酒店的地狱暗示,史蒂夫·布西密当中的化妆我觉得跟地狱的白无常还真有几分似。巴顿的房间有很多令人去揣测和解读的意向,墙上的那副蚊子、脱落的墙纸、还有那副美女海滩油画,无论蚊子还是墙纸,它们和要写的剧本把巴顿从肉体到精神上折磨得焦头烂额,片尾巴顿在海滩看见真实的美女海滩画面,问了一句:“are you in picture?”是一语双关,他觉得那么美的人应该是拍电影的吧。

本片饰演巴顿的约翰·特托罗固然演技精湛,实际上片中为数不多的演员都令人留下相当深刻的影响,查理的饰演者约翰·古德曼更是精彩之极。查理和巴顿一个胖一个瘦,查理是唯一能和巴顿谈得来的人,但他们第一次见面,查理问巴顿是写什么剧本的,巴顿可以打开话匣子滔滔不绝地说,甚至忘记对方的存在。如本文开篇所说,巴顿最终写出摔跤手与自己灵魂摔跤的故事,这说明查理不过是巴顿的灵魂,在片中我们也能看到查理和巴顿抱在一起摔跤的画面,那一幕的气氛拍得是有点诡异。

高安兄弟的电影没有大起大落的剧情,反高潮,这些都是十分反好莱坞的做法,《才子梦惊魂》更借故事内容再把好莱坞批判个遍。老板千辛万苦请你来好莱坞写电影剧本,就是要写类型片,写观众爱看,要有动作场面,一上来不要那么多内容先来场动作戏,但你最后却写出一个摔跤手和自己灵魂摔跤的故事,你自然是要帮老板“倒米”,片中老板对巴顿的态度前后对比真是相当鲜明。巴顿的好莱坞行也是一场幻灭之行,他看到很多好莱坞还有文化圈的丑恶,他发现自己最敬佩的作家原来是个酒鬼,而且他的作品竟然是代笔。高安兄弟透过巴顿这一次西行好莱坞,把她的虚伪和功利都进行无情的讽刺,这是二十多年前对好莱坞的态度。而反观当下,好莱坞的某些生态早就蔓延全球,尤其影响一些电影业后起蓬勃的强国,所以如今再看《才子梦惊魂》里面的那些讽刺的内容,在当下依然是那么有力。

《巴顿·芬克》观后感(八):接過希治閣衣缽的新緊張大師

Barton Fink《才子夢驚魂》,不是我喜歡的類型,但如雷貫耳的康城影展大滿貫(金棕櫚、最佳導演、男主角)肯定貨真價實。這個故事,一如高安兄弟的許多早期作品:人物少、情節精煉、非常專注在人物的心理狀況,張力與懸念就在細節當中。譽高安兄弟為新一代緊張大師,當之無愧。在乍看如此悶騷、缺乏動作與事件的劇情元素下,仍玩出步步驚心的氛圍,作為編劇學習對象,實是上佳之選。有說這片頗有自況意味,高安兄弟當時本在進行另一電影計劃,不巧陷入創作瓶頸,便把計劃放下,改寫這個反映當下心境之作。故事的主角正是一個簽了約卻寫不出荷李活俗片劇本的紐約舞台編劇,他的困惑、焦慮和不安漸變成各種說不出的恐懼,虛實不清的處境悄然上場,哪些是編劇的的惡夢?哪些才是現實?高手在於,高安兄弟讓你覺得根本沒所謂。

《巴顿·芬克》观后感(九):《巴頓芬克》-作家的存在與真實

網誌圖文版 http://zassili.blogspot.tw/2012/11/normal-0-0-2-microsoftinternetexplorer4.html_________________________________________________________________________

李不才第一次接觸柯恩兄弟(Joel Coen, Ethan Coen)的電影,是前兩年看《險路勿近》(No Country for Old Men, 2007)。看完的第一個反應是:這三小?除了妹妹頭殺手真的超殺外,我完全抓不住「No Country for Old Men」的意義。只看到表面上人類的愚蠢行徑,無法體會更深。多看幾篇評論後,才比較清晰地抓住導演意圖。有了這層心理準備,再看《冰血暴》(Fargo, 1996)、《謀殺綠腳指》(The Big Lebowski, 1998)、《霹靂高手》(O Brother, Where Art Thou?, 2000)等片,就跟得上導演思維,也樂在其中。

如果要對柯恩兄弟的電影,下一個核心定義,大概是對「存在」的提問。「存在」這個字眼很令人頭大,因為他所指涉的是廣博的「存在主義」思潮:與之直接相關或間接相關的,含哲學家沙特(Jean-Paul Sartre, 1905-1980)、海德格(Martin Heidegger, 1889- 1976),文學創作者卡繆(Albert Camus, 1913-1960)、貝克特(Samuel Beckett, 1906-1989)等等等。以李不才的智慧,去論述存在主義思潮,大概等同於搬101砸自己的腳。但輕輕略過這項問題,便去探討柯恩兄弟,也只是打打游擊,處理核心外緣。

雖說難以處理,但仍然有切入點,即《巴頓芬克》(Barton Fink, 1991)。《巴頓芬克》講述1940年代,在百老匯獲得成功的青年劇作家芬克,投身好萊塢這個造夢工廠。芬克理想中的表演藝術,是創作「屬於民眾」的戲劇,跨越劇場被歸類為高等育樂的藩籬,走進市井百姓生活中。對照美國的戲劇發展史,這倒不是什麼新鮮的觀念:相對於歐洲的前衛藝術,美國戲劇圈在二十世紀上半葉,一直處於被動接受的位置—當美國表演圈摸索學習寫實主義技巧時,歐陸已轉向非寫實發展。

美國寫實主義戲劇中,又以「基層群眾」為主要對象。重要的劇作家尤金奧尼爾(Eugene O'Neill)、桑頓懷爾德(Thornton Wilder)、田納西威廉斯(Tennessee William)、亞瑟米勒(Arthur Miller)皆關注於此—巴頓芬克所設想的「脫離抽象象徵等無聊裝飾,屬於群眾的劇場」,便是這個傳統的產物。

為何寫實主義創作,被賦予這麼嚴肅的創作意圖?嚴格規範的寫實主義寫作,誕生於十九世紀上半葉,主要作家有巴爾札克(Honore de Balzac)、福樓拜(Gustave Flaubert)、莫伯桑(Guy de Maupassant)、狄更斯(Charles Dickens)等。他們的取材上至王公貴族,下至世井百姓,只有一個要求—「描寫一個時代的真實」。這項傳統自巴爾札克起,便形成延續至今的社會記實瘋狂計畫:巴爾札克的《人間喜劇》(Comédie Humaine)系列(註:《人間喜劇》分為三大部分:風俗研究、哲理研究、分析研究,原計畫完成137部小說,實際完成91部)、左拉(Émile Zola, 1840-1902)的自然主義寫作《盧貢·馬加爾家族—第二帝國時代一個家族的自然史和社會史》(註:共二十部系列作,含名著《酒店》、《娜娜》)、高爾斯華綏(John Galsworthy)的《福爾賽世家》三部曲、福克那(William Faulkner)終生經營的虛擬南方小鎮、厄普戴克(John Updike)每十年一部描寫美國中產階級的「兔子四部曲」。這些創作,目的在呈現特定時空中,各階層所處的環境與意向。

還原「寫實主義」創立的歷史現場,「描繪真實」的訴求除了藝術風格的自新規律外(如浪漫主義反古典主義),時空背景的巨變更為重要:從古典社會走向現代化,產生許多變動:宗教權力讓位於世俗權力、君權讓位於民權(或者說是官僚集團)、一級產業與手工業讓位於工廠工業、地域性貿易讓位於全球貿易、珍藏書籍讓位於隨手可見的報刊。這些變化的總合,使知識份子原先認識的世界變得四分五裂,同時瓦解了他們原先的信仰核心。如此,失去政治與現實依憑的知識份子,便開始尋找新的核心價值。

現代化提升群眾地位,工業化與自由貿易亦使民眾的信仰與民生問題,組成複雜糾葛的網絡。也因此,知識份子轉進民眾之中。當然,上述文字只是一種概述,許多的藝術流派仍深處高端,精細雕琢玻璃球內的世界;保守的社會輿論仍不友善的對待任何具「革命性」的創新(按:如1857年,《包法利夫人》因「內容誨淫」而被送上法院【所謂誨淫大概等同於「每逢育昇,想起薇閣」之通姦題材】)。但「民生」進入藝文體裁中,已是不可逆的現象。

寫實主義的並非就此一統天下,「反寫實」的聲浪到今日仍是「前衛藝術」的神主牌。他們不滿足只是忠實反應表面現實,試圖挖掘不同的關係:可能是個人處境的自我分裂、或者將世界視為陌生的他者、或根本否定時空與個人的關係中,是否有直接的邏輯關係。以卡夫卡與卡繆為例。卡夫卡與卡繆的主人公,總是「人間他者」:莫名遭受審判的K、睡醒變成巨大昆蟲的男子、意外殺人入獄的異鄉人。他們身處的環境,反映社會的敵意與不可解。有趣的是,「人間他者」不是文壇的孤立現象:自進入現代化後,作家所感知的「自我」與「社會」的對立,成為承續數代人的「全球化形象」:如芥川龍之芥〈一個傻瓜的一生〉、太宰治《人間失格》、俄羅斯文學中「多餘的人(註:吃飽閒閒的有錢青年貴族,與上流社會格格不入,卻無力亦無勇氣反抗者)」。當參與、詮釋皆不可能,人就只剩下「自己的存在」。

阿哩阿匝扯了這麼多,敏銳的朋友應該已經感受到,上述文字與《巴頓芬克》的關係。《巴頓芬克》惡質的黑色幽默,便是將寫實主義式的人物(作家芬克),丟入反寫實的語境中。寫實主義創作中,小說人物面對各種困境(戰爭、經濟困境、妻子偷人、亂倫),他們的反應與環境變動,始終是「有邏輯關係的變化(精確的說,是創作者所認知的社會反應)」。但在「非寫實」的環境中,不同的環境彼此無直接的聯繫,分裂為不同的單元。這些分裂的單元又共同組織動員,不斷攻擊、威脅角色,讓他越來越遠離「世人習慣的社會(按:用一個不好的比喻:當一個「正常人」,被打上罪犯、精神病患、窮鬼、非異性戀者等非主流的印記,那他就脫離「正常人」,而進入「局外人」的角色)」。

回過頭來看看巴頓芬克所遇到人事物:只見利益,鼓動芬克前往好萊塢的劇場經濟人;全然不關心藝術價值,帶有法西斯色彩的蠻橫片商;維維諾諾、毫無尊嚴的破產者;沒有言語、沒有情緒,像殭屍的電梯服務員;昔日偉大的劇作家,現沉浮於好萊塢,靠酒精創作垃圾電影劇本;徐娘半老,「偉大劇作家」的秘書兼幕後代筆人;最後也是最重要的,巴頓投宿的飯店鄰居:假扮為保險業務的胖子殺人魔。原本擁有理想抱負、眼中噴出雷射光的巴頓(按:李不才多方接觸各類NGO與藝文組織的工作者,最害怕的就是眼中發出理想火焰焚燒我污濁靈魂的有理想有抱負的青年),在怪誕的人群中,捲入連串荒謬事件中:先是自我質疑、理想破滅。最後甚至否定過往的自我存在,拋下一生建立的世界觀,赤裸裸而獨身的重新面對世界-就此而言,巴頓真的碰觸到了他理想中的真實-「荒謬無序」。

知識份子的理想破滅並不是新穎的題材。但為何柯恩兄弟要將追求真實的作家,投入荒謬語境裡?故事的起點是,「如何說一個故事」。李不才多年損友偉偉公,是薄有微名的新銳作家。不才是不知名不自由寫作者。我與偉偉公的對話中,對生活出現的人、事、物,是以「人」、「事」、「物」,加上引號後,經過整理與批判解讀,歸類在「寫作資料庫」。這裡以偉偉公的劣行為例:當偉偉公與天真無邪的小朋友聊天時,他關注的是該名兒童的特殊背景,並誘導發問,以取得所需的訊息。這種暗自進行的「私人採訪」行為,是創作者的創作泉源,是他們所構築的「真實」—「人」、「事」、「物」材料堆組的大廈。

用較為嚴苛地道德標準批判,這種行為可稱對他人生命深吞活剥的惡劣侵犯。電影中,巴頓問胖子殺人魔為何選上他,胖子殺人魔的回答卻直攻所有的「採訪者」、「創作者」、「侵犯他人生活者」、「無同理心卻假意關注他人者」:

「你認為你知道痛苦?你認為我讓你的生活痛苦?看看這個垃圾地方,你只是個帶打

字機的旅客,我住在這,你不明白嗎?你來到我的家,你抱怨,我弄出太多噪音。」

親切可愛帶點惱人的胖子殺人魔,在片尾的獨白 中,顯現他與巴頓的相似與矛盾:殺人魔敏銳察覺每個人的心理殘缺,並感同身受。巴頓站在知識份子的偷窺者位置,好整以暇地「觀察現實」。殺人魔介入每個他 同情的人事物,並試圖改善他們的處境(雖然方法是讓他們「蒙主感召」);巴頓則是在發現好題材後,準備用「書寫」來感招世人。殺人魔活在巴頓所說的「真實」的垃圾堆中,巴頓卻是個帶著打字機的旅客。這也是為何在片尾火場中,巴頓轉身離去,殺人魔卻回到他的「家」。

巴頓一心希望追求偉大的劇作:愚蠢的片商、衰頹的文壇領袖、二流的旅館、只見利益的經濟人、仍有誘惑力的作家秘書,一切的一切都不能幫助他寫出理想的作品。卻是在胖子殺人魔栽贓巴頓殺人後,巴頓面對接踵而來的荒謬,才首次真正面對了「(荒謬無序的)真實」。當他將所思所感,寫出最滿意的劇作時,卻毫無意外地被片商視為垃圾(在此我們看到老劇作家的身影)。

柯恩兄弟以其慣用的黑色幽默,諷刺試圖站在真實外緣、卻大吼大叫以真實為創作核心的作家(這裡頭自然也包含了脫離生活、享用過去所累積的文化資本濫情創作者)。但對於真實的真正信徒,柯恩兄弟也給我們一個深具寓意的圖像:火焰中的獨行者。

◎有關存在主義與卡繆「局外人」的論述,請見 《逃離惡魔島》-卡繆的反抗者

《巴顿·芬克》观后感(十):你们写个鸡吧影评?直接抄维基算了?需要翻译请留言

Barton FinkFrom Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to: navigation, search

Barton Fink

BartonFink.jpg

Theatrical release poster

Directed by

Joel Coen

Produced by

Ethan Coen

Written by

Joel Coen

Ethan Coen

Starring

John Turturro

John Goodman

Music by

Carter Burwell

Cinematography

Roger Deakins

Editing by

Joel Coen

Ethan Coen

(as Roderick Jaynes)

Studio

Circle Films

Working Title Films

Distributed by

20th Century Fox

Release dates

May 1991 (Cannes)

August 21, 1991

Running time

116 minutes[1]

Country

United States

Language

English

Budget

$9 million

Box office

$6,153,939

Barton Fink is a 1991 American period film written, directed, produced, and edited by the Coen brothers. Set in 1941, it stars John Turturro in the title role as a young New York City playwright who is hired to write scripts for a film studio in Hollywood, and John Goodman as Charlie, the insurance salesman who lives next door at the run-down Hotel Earle.

The Coens wrote the screenplay in three weeks while experiencing difficulty during the writing of Miller's Crossing. Soon after Miller's Crossing was finished, the Coens began filming Barton Fink, which had its premiere at the Cannes Film Festival in May 1991. In a rare sweep, Barton Fink won the Palme d'Or, as well as awards for Best Director and Best Actor (Turturro). Although it was celebrated almost universally by critics and nominated for three Academy Awards, the film grossed only a little over $6 million at the box office, two-thirds of its estimated budget.

The process of writing and the culture of entertainment production are two prominent themes of Barton Fink. The world of Hollywood is contrasted with that of Broadway, and the film analyzes superficial distinctions between high culture and low culture. Other themes in the film include fascism and World War II; slavery and conditions of labor in creative industries; and how intellectuals relate to "the common man". Because of its diverse elements, the film has defied efforts at genre classification, being variously referred to as a film noir, a horror film, a Künstlerroman, and a buddy film.

The feel of the Hotel Earle was central to the development of the story, and careful deliberation went into its design. There is a sharp contrast between Fink's living quarters and the polished, pristine environs of Hollywood, especially the home of Jack Lipnick. On the wall of Fink's room there hangs a single picture of a woman at the beach; this captures Barton's attention, and the image reappears in the final scene of the film. Although the picture and other elements of the film (including a mysterious box given to Fink by Charlie) appear laden with symbolism, critics disagree over their possible meanings. The Coens have acknowledged some intentional symbolic elements while denying an attempt to communicate some holistic message.

The film contains allusions to many real-life people and events, most notably the writers Clifford Odets and William Faulkner. The characters of Barton Fink and W. P. Mayhew are widely seen as fictional representations of these men, but the Coens stress important differences. They have also admitted to parodying film magnates like Louis B. Mayer, but they note that Fink's agonizing tribulations in Hollywood are not meant to reflect their own experiences.

Barton Fink was influenced by several earlier works, including the films of Roman Polanski, particularly Repulsion (1965) and The Tenant (1976). Other influences are Stanley Kubrick's The Shining and Preston Sturges's Sullivan's Travels. The film contains a number of literary allusions to works by William Shakespeare, John Keats, and Flannery O'Connor. There are also religious overtones, including references to the Book of Daniel, King Nebuchadnezzar, and Bathsheba.

Contents [hide]

1 Plot

2 Cast

3 Production 3.1 Background and writing

3.2 Filming

3.3 Setting 3.3.1 The Picture

4 Genre

5 Style 5.1 Symbolism

5.2 Sound and music

6 Sources, inspirations, and allusions 6.1 Clifford Odets

6.2 William Faulkner

6.3 Jack Lipnick

6.4 Cinema

7 Themes 7.1 Broadway and Hollywood

7.2 Writing

7.3 Fascism

7.4 Slavery

7.5 "The Common Man"

7.6 Religion

8 Reception

9 Possible sequel

10 References

11 External links

Plot[edit]

In 1941, Barton Fink is enjoying the success of his first Broadway play, Bare Ruined Choirs. His agent informs him that Capitol Pictures in Hollywood has offered him a thousand dollars per week to write film scripts. Barton hesitates, worried that moving to California would separate him from "the common man," his focus as a writer. He accepts the offer, however, and checks into the Hotel Earle, a large and unusually deserted building. His room is sparse and draped in subdued colors; its only decoration is a small painting of a woman on the beach, arm raised to block the sun.

In his first meeting with Capitol Pictures boss Jack Lipnick, Barton explains that he chose the Earle because he wants lodging that is (as Lipnick says) "less Hollywood." Lipnick promises that his only concern is Barton's writing ability and assigns his new employee to a wrestling film. Back in his room, however, Barton is unable to write. He is distracted by sounds coming from the room next door, and he phones the front desk to complain. His neighbor, Charlie Meadows, is the source of the noise and visits Barton to apologize, insisting on sharing some alcohol from a hip flask to make amends. As they talk, Barton proclaims his affection for "the common man," and Charlie describes his life as an insurance salesman. Later, Barton falls asleep, but is awoken by the incessant whine of a mosquito.

Still unable to proceed beyond the first lines of his script, Barton consults producer Ben Geisler for advice. Irritated, the frenetic Geisler takes him to lunch and orders him to speak with another writer for assistance. While in the bathroom, Barton meets the novelist William Preston (W.P.) "Bill" Mayhew, who is vomiting in the next stall. They briefly discuss movie writing and arrange a second meeting later in the day. When Barton arrives, Mayhew is drunk and yelling wildly. His secretary, Audrey Taylor, reschedules the meeting and confesses to Barton that she and Mayhew are in love. When they finally meet for lunch, Mayhew, Audrey, and Barton discuss writing and drinking. Before long, Mayhew argues with Audrey, slaps her and wanders off, drunk. Rejecting Barton's offer of consolation, she explains that she feels sorry for Mayhew since he is married to another woman who is "disturbed."

The Coen brothers wrote the role of Charlie Meadows for actor John Goodman, in part because of the "warm and friendly image that he projects for the viewer".[2]

With one day left before his meeting with Lipnick to discuss the movie, Barton phones Audrey and begs her for assistance. She visits him at the Earle, and after she admits that she wrote most of Mayhew's scripts, they are assumed to have sex; Barton later confesses to Charlie they did so. When he wakes up the next morning, he, again, hears the sound of the mosquito, finds it on Audrey's back, and slaps it dead. When Audrey does not respond, he turns her onto her side only to find that she has been violently murdered. He has no memory of the night's events. Horrified, he summons Charlie and asks for help. Charlie is repulsed but disposes of the body and orders Barton to avoid contacting the police. After a meeting with an unusually supportive Lipnick, Barton tries writing again and is interrupted by Charlie, who announces he is going to New York for several days. Charlie leaves a package with Barton and asks him to watch it.

Soon afterward, Barton is visited by two police detectives, who inform him that Charlie's real name is Karl Mundt – "Madman Mundt." He is a serial killer wanted for several murders; after shooting his victims, they explain, he decapitates them and keeps the heads. Stunned, Barton returns to his room and examines the box. Placing it on his desk without opening it, he begins writing and produces the entire script in one sitting. After a night of celebratory dancing, Barton returns to find the detectives in his room, who, after handcuffing him to the bed, then reveal Mayhew's murder. Charlie appears, and the hotel is engulfed in flames. Running through the hallway, screaming, Charlie shoots the policemen with a shotgun. As the hallway burns, Charlie speaks with Barton about their lives and the hotel, breaks the bed frame Barton is cuffed to, then retires to his own room, saying as he goes that he has paid a visit to Barton's parents and uncle in New York. Barton leaves the hotel, carrying the box and his script. Shortly thereafter he attempts to telephone his parents, but there is no answer.

In a final meeting, a disappointed Lipnick, in uniform as he attempts to secure an Army reserve commission, angrily chastises Barton for writing "a fruity movie about suffering," then informs him that he is to remain in Los Angeles, and that – although he will remain under contract – Capitol Pictures will not produce anything he writes so he can be ridiculed as a loser around the studio while Lipnick is in the war. Dazed, Barton wanders onto a beach, still carrying the package. He meets a woman who looks just like the one in the picture on his wall at the Earle, and she asks about the box. He tells her that he knows neither what it contains nor to whom it belongs. She assumes the pose from the picture.

Cast[edit]

##John Turturro as Barton Fink

##John Goodman as Charlie Meadows

##Michael Lerner as Jack Lipnick

##Judy Davis as Audrey Taylor

##John Mahoney as W. P. Mayhew

##Tony Shalhoub as Ben Geisler

##Jon Polito as Lou Breeze

##Steve Buscemi as Chet

##David Warrilow as Garland Stanford

##Richard Portnow as Detective Mastrionotti

##Christopher Murney as Detective Deutsch

##Megan Fay as Poppy Carnahan

##Lance Davis as Richard St. Claire

##Frances McDormand as Voice of stage actress (uncredited)

##Barry Sonnenfeld as Page (uncredited)

Production[edit]

Background and writing[edit]

In 1989, filmmakers Joel and Ethan Coen began writing the script for a film eventually released as Miller's Crossing. The many threads of the story became complicated, and after four months they found themselves lost in the process.[3] Although biographers and critics later referred to it as writer's block,[4] the Coen brothers rejected this description. "It's not really the case that we were suffering from writer's block," Joel said in a 1991 interview, "but our working speed had slowed, and we were eager to get a certain distance from Miller's Crossing."[5] They went from Los Angeles to New York and began work on a different project.[6]

The Coen brothers said of writing Barton Fink: "We didn't do any research, actually, at all."[7]

In three weeks, the Coens wrote a script with a title role written specifically for actor John Turturro, with whom they'd been working on Miller's Crossing. The new movie, Barton Fink, was set in a large, seemingly-abandoned hotel.[5] This setting, which they named the Hotel Earle, was a driving force behind the story and mood of the new project. While filming their 1984 film Blood Simple in Austin, Texas, the Coens had seen a hotel which made a significant impression: "We thought, 'Wow, Motel Hell.' You know, being condemned to live in the weirdest hotel in the world."[8]

The writing process for Barton Fink was smooth, they said, suggesting that the relief of being away from Miller's Crossing may have been a catalyst. They also felt satisfied with the overall shape of the story, which helped them move quickly through the composition. "Certain films come entirely in one's head; we just sort of burped out Barton Fink."[9] While writing, the Coens created a second leading role with another actor in mind: John Goodman, who had appeared in their 1987 comedy Raising Arizona. His new character, Charlie, was Barton's next-door neighbor in the cavernous hotel.[10] Even before writing, the Coens knew how the story would end, and wrote Charlie's final speech at the start of the writing process.[11]

The script served its diversionary purpose, and the Coens put it aside: "Barton Fink sort of washed out our brain and we were able to go back and finish Miller's Crossing."[12] Once production of the first movie was finished, the Coens began to recruit staff to film Barton Fink. Turturro looked forward to playing the lead role, and spent a month with the Coens in Los Angeles to coordinate views on the project: "I felt I could bring something more human to Barton. Joel and Ethan allowed me a certain contribution. I tried to go a little further than they expected."[13]

As they designed detailed storyboards for Barton Fink, the Coens began looking for a new cinematographer, since their associate Barry Sonnenfeld – who had filmed their first three movies – was occupied with his own directorial debut, The Addams Family. The Coens had been impressed with the work of English cinematographer Roger Deakins, particularly the interior scenes of the 1988 film Stormy Monday. After screening other films he had worked on (including Sid and Nancy and Pascali's Island), they sent a script to Deakins and invited him to join the project. His agent advised against working with the Coens, but Deakins met with them at a cafe in Notting Hill and they soon began working together on Barton Fink.[14]

Filming[edit]

Restaurant scenes set in New York at the start of Barton Fink were filmed inside the RMS Queen Mary ocean liner.[10]

Filming began in June 1990 and took eight weeks (a third less time than required by Miller's Crossing), and the estimated final budget for the movie was US$9 million.[15] The Coens worked well with Deakins, and they easily translated their ideas for each scene onto film. "There was only one moment we surprised him," Joel Coen recalled later. An extended scene called for a tracking shot out of the bedroom and into a sink drain "plug hole" in the adjacent bathroom as a symbol of sexual intercourse. "The shot was a lot of fun and we had a great time working out how to do it," Joel said. "After that, every time we asked Roger to do something difficult, he would raise an eyebrow and say, 'Don't be having me track down any plug-holes now.'"[16]

Three weeks of filming were spent in the Hotel Earle, a set created by art director Dennis Gassner. The film's climax required a huge spreading fire in the hotel's hallway, which the Coens originally planned to add digitally in post-production. When they decided to use real flames, however, the crew built a large alternate set in an abandoned aircraft hangar at Long Beach. A series of gas jets were installed behind the hallway, and the wallpaper was perforated for easy penetration. As Goodman ran through the hallway, a man on an overhead catwalk opened each jet, giving the impression of a fire racing ahead of Charlie. Each take required a rebuild of the apparatus, and a second hallway (sans fire) stood ready nearby for filming pick-up shots between takes.[15] The final scene was shot near Zuma Beach, as was the image of a wave crashing against a rock.[10]

The Coens edited the film themselves, as is their custom. "We prefer a hands-on approach," Joel explained in 1996, "rather than sitting next to someone and telling them what to cut."[17] Because of rules for membership in film production guilds, they are required to use a pseudonym; "Roderick Jaynes" is credited with editing Barton Fink.[18] Only a few filmed scenes were removed from the final cut, including a transition scene to show Barton's movement from New York to Hollywood. (In the movie, this is shown enigmatically with a wave crashing against a rock.) Several scenes representing work in Hollywood studios were also filmed, but edited out because they were "too conventional".[19]

Setting[edit]

The peeling wallpaper in Barton's room was designed to mimic the pus dripping from Charlie's infected ear.[20]

The spooky, inexplicably empty feel of the Hotel Earle was central to the Coens' conception of the movie. "We wanted an art deco stylization," Joel explained in a 1991 interview, "and a place that was falling into ruin after having seen better days."[20] Barton's room is sparsely furnished with two large windows facing another building. The Coens later described the hotel as a "ghost ship floating adrift, where you notice signs of the presence of other passengers, without ever laying eyes on any". In the movie, residents' shoes are an indication of this unseen presence; another rare sign of other inhabitants is the sound from adjacent rooms.[21] Joel said: "You can imagine it peopled by failed commercial travelers, with pathetic sex lives, who cry alone in their rooms."[20] Heat and moisture are other important elements of the setting. The wallpaper in Barton's room peels and droops; Charlie experiences the same problem, and guesses heat is the cause. The Coens used green and yellow colors liberally in designing the hotel "to suggest an aura of putrefaction".[20]

The atmosphere of the hotel was meant to connect with the character of Charlie. As Joel explained: "Our intention, moreover, was that the hotel function as an exteriorization of the character played by John Goodman. The sweat drips off his forehead like the paper peels off the walls. At the end, when Goodman says that he is a prisoner of his own mental state, that this is like some kind of hell, it was necessary for the hotel to have already suggested something infernal."[20] The peeling wallpaper and the paste which seeps through it also mirror Charlie's chronic ear infection and the resultant pus.[22]

When Barton first arrives at the Hotel Earle, he is asked by the friendly bellhop Chet (Steve Buscemi) if he is "a trans or a res" – transient or resident. Barton explains that he isn't sure, but will be staying "indefinitely".[23] The dichotomy between permanent inhabitants and guests reappears several times, notably in the hotel's motto, "A day or a lifetime", which Barton notices on the room's stationery. This idea returns at the end of the movie, when Charlie describes Barton as "a tourist with a typewriter". His ability to leave the Earle (while Charlie remains) is presented by critic Erica Rowell as evidence that Barton's story represents the process of writing itself. Barton, she says, represents an author who is able to leave a story, while characters like Charlie cannot.[22]

The Coens chose to set Barton Fink at the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor to indicate that "the world outside the hotel was finding itself on the eve of the apocalypse".[5]

In contrast, the offices of Capitol Pictures and Lipnick's house are pristine, lavishly decorated, and extremely comfortable. The company's rooms are bathed in sunlight, and Ben Geisler's office faces a lush array of flora. Barton meets Lipnick in one scene beside an enormous, spotless swimming pool. This echoes his position as studio head, as he explains: "...you can't always be honest, not with the sharks swimming around this town ... if I'd been totally honest, I wouldn't be within a mile of this pool – unless I was cleaning it."[24] In his office, Lipnick showcases another trophy of his power: statues of Atlas, the Titan of Greek mythology who declared war on the gods of Mount Olympus and was severely punished.[25]

Barton watches dailies from another wrestling film being made by Capitol Pictures; the date on the clapperboard is 9 December, two days after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Later, when Barton celebrates the completed script by dancing at a USO show, he is surrounded by soldiers.[26] In Lipnick's next appearance, he wears a colonel's uniform, which is really a costume from his company. Lipnick has not actually entered the military, but declares himself ready to fight the "little yellow bastards".[27] Originally, this historical moment just after the United States entered World War II was to have a significant impact on the Hotel Earle. As the Coens explained: "[W]e were thinking of a hotel where the lodgers were old people, the insane, the physically handicapped, because all the others had left for the war. The further the script was developed, the more this theme got left behind, but it had led us, in the beginning, to settle on that period."[28]

The Picture[edit]

Ethan Coen said in a 1991 interview that the woman on the beach in Barton's room (above) was meant to give "the feeling of consolation".[29] One critic calls her presence in the final scene (below) "a parody of form".[30]

The picture in Barton's room of a woman at the beach is a central focus for both the character and camera. He examines it frequently while at his desk, and after finding Audrey's corpse in his bed he goes to stand near it. The image is repeated at the end of the film, when he meets an identical-looking woman at an identical-looking beach, who strikes an identical pose. After complimenting her beauty, he asks her: "Are you in pictures?" She blushes and replies: "Don't be silly."[31]

The Coens decided early in the writing process to include the picture as a key element in the room. "Our intention," Joel explained later, "was that the room would have very little decoration, that the walls would be bare and that the windows would offer no view of any particular interest. In fact, we wanted the only opening on the exterior world to be this picture. It seemed important to us to create a feeling of isolation."[32]

Later in the film, Barton places into the frame a small picture of Charlie, dressed in a fine suit and holding a briefcase. The juxtaposition of his neighbor in the uniform of an insurance salesman and the escapist image of the woman on the beach leads to a confusion of reality and fantasy for Barton. Critic Michael Dunne notes: "[V]iewers can only wonder how 'real' Charlie is. ... In the film's final shot ... viewers must wonder how 'real' [the woman] is. The question leads to others: How real is Fink? Lipnick? Audrey? Mayhew? How real are films anyway?"[33]

The picture's significance has been the subject of broad speculation. Washington Post reviewer Desson Howe said that despite its emotional impact, the final scene "feels more like a punchline for punchline's sake, a trumped-up coda".[34] In her book-length analysis of the Coen brothers' films, Rowell suggests that Barton's fixation on the picture is ironic, considering its low culture status and his own pretensions toward high culture (speeches to the contrary notwithstanding). She further notes that the camera focuses on Barton himself as much as the picture while he gazes at it. At one point, the camera moves past Barton to fill the frame with the woman on the beach. This tension between objective and subjective points of view appears again at the end of the film, when Barton finds himself – in a sense – inside the picture.[35]

Critic M. Keith Booker calls the final scene an "enigmatic comment on representation and the relationship between art and reality". He suggests that the identical images point to the absurdity of art which reflects life directly. The film transposes the woman directly from art to reality, prompting confusion in the viewer; Booker asserts that such a literal depiction therefore leads inevitably to uncertainty.[36]

Genre[edit]

The Coens are known for making films that defy simple classification. Although they refer to their first film, Blood Simple, as a relatively straightforward example of detective fiction, the Coens wrote their next script, Raising Arizona, without trying to fit a particular genre. They decided to write a comedy, but intentionally added dark elements to produce what Ethan calls "a pretty savage film".[37] Their third film, Miller's Crossing, reversed this order, mixing bits of comedy into a crime film. Yet it also subverts single-genre identity by using conventions from melodrama, love stories, and political satire.[38]

This trend of mixing genres continued and intensified with Barton Fink; the Coens insist the film "does not belong to any genre".[2] Ethan has described it as "a buddy movie for the '90s".[39] It contains elements of comedy, film noir, and horror, but other film categories are present.[40] Actor Turturro referred to it as a coming of age story,[39] while literature professor and film analyst R. Barton Palmer calls it a Künstlerroman, highlighting the importance of the main character's evolution as a writer.[41] Critic Donald Lyons describes the movie as "a retro-surrealist vision".[42]

Because it crosses genres, fragments the characters' experiences, and resists straightforward narrative resolution, Barton Fink is often considered an example of postmodernist film. In his book Postmodern Hollywood, Booker says the movie renders the past with an impressionist technique, not a precise accuracy. This technique, he notes, is "typical of postmodern film, which views the past not as the prehistory of the present but as a warehouse of images to be raided for material".[43] In his analysis of the Coens' films, Palmer calls Barton Fink a "postmodern pastiche" which closely examines how past eras have represented themselves. He compares it to The Hours, a 2002 film about Virginia Woolf and two women who read her work. He asserts that both films, far from rejecting the importance of the past, add to our understanding of it. He quotes literary theorist Linda Hutcheon: The kind of postmodernism exhibited in these films "does not deny the existence of the past; it does question whether we can ever know that past other than through its textualizing remains".[44]

Certain elements in Barton Fink highlight the veneer of postmodernism: the writer is unable to resolve his modernist focus on high culture with the studio's desire to create formulaic high-profit films; the resulting collision produces a fractured story arc emblematic of postmodernism.[45] The Coens' cinematic style is another example; when Barton and Audrey begin making love, the camera pans away to the bathroom, then moves toward the sink and down its drain. Rowell calls this a "postmodern update" of the notorious sexually suggestive image of a train entering a tunnel, used by director Alfred Hitchcock in his 1959 film North by Northwest.[46]

Style[edit]

The influence of filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock appears several times in the movie. In one scene, Barton's eyeglasses reflect a wrestling scene; this echoes a shot from Hitchcock's 1946 film Notorious.[47]

Barton Fink uses several stylistic conventions to accentuate the story's mood and give visual emphasis to particular themes. For example, the opening credits roll over the Hotel Earle's wallpaper, as the camera moves downward. This motion is repeated many times in the film, especially pursuant to Barton's claim that his job is to "plumb the depths" while writing.[35] His first experiences in the Hotel Earle continue this trope; the bellhop Chet emerges from beneath the floor, suggesting the real activity is underground. Although Barton's floor is presumably six floors above the lobby, the interior of the elevator is shown only while it is descending. These elements – combined with many dramatic pauses, surreal dialogue, and implied threats of violence – create an atmosphere of extreme tension. The Coens explained that "the whole movie was supposed to feel like impending doom or catastrophe. And we definitely wanted it to end with an apocalyptic feeling".[48]

The style of Barton Fink is also evocative – and representative – of films of the 1930s and '40s. As critic Michael Dunne points out: "Fink's heavy overcoat, his hat, his dark, drab suits come realistically out of the Thirties, but they come even more out of the films of the Thirties."[49] The style of the Hotel Earle and atmosphere of various scenes also reflect the influence of pre-WWII filmmaking. Even Charlie's underwear matches that worn by his film-ic hero Jack Oakie. At the same time, camera techniques used by the Coens in Barton Fink represent a combination of the classic with the original. Careful tracking shots and extreme close-ups distinguish the film as a product of the late 20th century.[50]

From the start, the film moves continuously between Barton's subjective view of the world and one which is objective. After the opening credits roll, the camera pans down to Barton, watching the end of his play. Soon we see the audience from his point of view, cheering wildly for him. As he walks forward, he enters the shot and the viewer is returned to an objective point of view. This blurring of the subjective and objective returns in the final scene.[51]

The shifting point of view coincides with the movie's subject matter: filmmaking. The film begins with the end of a play, and the story explores the process of creation. This metanarrative approach is emphasized by the camera's focus in the first scene on Barton (who is mouthing the words spoken by actors offscreen), not on the play he is watching. As Rowell says: "[T]hough we listen to one scene, we watch another. ... The separation of sound and picture shows a crucial dichotomy between two 'views' of artifice: the world created by the protagonist (his play) and the world outside it (what goes into creating a performance)."[52]

The film also employs numerous foreshadowing techniques. Signifying the probable contents of the package Charlie leaves with Barton, the word "head" appears sixty times in the original screenplay.[53] In a grim nod to later events, Charlie describes his positive attitude toward his "job" of selling insurance: "Fire, theft and casualty are not things that only happen to other people."[54]

Symbolism[edit]

Much has been written about the symbolic meanings of Barton Fink. Rowell proposes that it is "a figurative head swelling of ideas that all lead back to the artist".[54] The proximity of the sex scene to Audrey's murder prompts Lyons to insist: "Sex in Barton Fink is death."[55] Others have suggested that the second half of the movie is an extended dream sequence.[29]

The Coens, however, have denied any intent to create a systematic unity from symbols in the film. "We never, ever go into our films with anything like that in mind," Joel said in a 1998 interview. "There's never anything approaching that kind of specific intellectual breakdown. It's always a bunch of instinctive things that feel right, for whatever reason."[56] The Coens have noted their comfort with unresolved ambiguity. Ethan said in 1991: "Barton Fink does end up telling you what's going on to the extent that it's important to know ... What isn't crystal clear isn't intended to become crystal clear, and it's fine to leave it at that."[57] Regarding fantasies and dream sequences, he said:

It is correct to say that we wanted the spectator to share in the interior life of Barton Fink as well as his point of view. But there was no need to go too far. For example, it would have been incongruous for Barton Fink to wake up at the end of the film and for us to suggest thereby that he actually inhabited a reality greater than what is depicted in the film. In any case, it is always artificial to talk about "reality" in regard to a fictional character.[29]

The homoerotic overtones of Barton's relationship with Charlie are not unintentional. Although one detective demands to know if they had "some sick sex thing", their intimacy is presented as anything but deviant, and cloaked in conventions of mainstream sexuality. Charlie's first friendly overture toward his neighbor, for example, comes in the form of a standard pick-up line: "I'd feel better about the damned inconvenience if you'd let me buy you a drink."[58] The wrestling scene between Barton and Charlie is also cited as an example of homoerotic affection. "We consider that a sex scene," Joel Coen said in 2001.[59]

Sound and music[edit]

Many of the sound effects in Barton Fink are laden with meaning. For example, Barton is summoned by a bell while dining in New York; its sound is light and pleasant. By contrast, the eerie sustained bell of the Hotel Earle rings endlessly through the lobby, until Chet silences it.[60] The nearby rooms of the hotel emit a constant chorus of guttural cries, moans, and assorted unidentifiable noises. These sounds coincide with Barton's confused mental state, and punctuate Charlie's claim that "I hear everything that goes on in this dump".[46] The applause in the first scene foreshadows the tension of Barton's move west, mixed as it is with the sound of an ocean wave crashing – an image which is shown onscreen soon thereafter.[61]

The Coen brothers were contacted by "the ASPCA or some animal thing" before filming began. "They'd gotten hold of a copy of the script and wanted to know how we were going to treat the mosquitoes. I'm not kidding."[62]

Another symbolic sound is the hum of a mosquito. Although his producer insists that these parasites don't live in Los Angeles (since "mosquitos breed in swamps; this is a desert"[63]), its distinctive sound is heard clearly as Barton watches a bug circle overhead in his hotel room. Later, he arrives at meetings with mosquito bites on his face. The insect also figures prominently into the revelation of Audrey's death; Barton slaps a mosquito feeding on her corpse, and suddenly realizes she's been murdered. The high pitch of the mosquito's hum is echoed in the high strings used for the movie's score.[64] During filming, the Coens were contacted by an animal rights group who expressed concern about how mosquitoes would be treated.[62]

The score was composed by Carter Burwell, who has worked with the Coens since their first film. Unlike earlier projects, however – the Irish folk tune used for Miller's Crossing and an American folk song as the basis for Raising Arizona – Burwell wrote the music for Barton Fink without a specific inspiration.[65] The score was released in 1996 on a compact disc, combined with the score for the Coens' film Fargo.[66]

Several songs used in the film are laden with meaning. At one point Mayhew stumbles away from Barton and Audrey, drunk. As he wanders, he hollers the folk song "Old Black Joe". Composed by Stephen Foster, it tells the tale of an elderly slave preparing to join his friends in "a better land". Mayhew's rendition of the song coincides with his condition as an oppressed employee of Capitol Pictures; it foreshadows Barton's own situation at the movie's end.[67]

When he finishes writing his script, Barton celebrates by dancing at a USO show. The song used in this scene is a rendition of "Down South Camp Meeting", a swing tune. Its lyrics (unheard in the film) state: "Git ready (Sing) / Here they come! The choir's all set." These lines echo the title of Barton's play, Bare Ruined Choirs. As the celebration erupts into a melee, the intensity of the music increases, and the camera zooms into the cavernous hollow of a trumpet. This sequence mirrors the camera's zoom into a sink drain just before Audrey is murdered earlier in the film.[26]

Sources, inspirations, and allusions[edit]

Inspiration for the film came from several sources, and it contains allusions to many different people and events. At one point in the picnic scene, as Mayhew wanders drunkenly away from Barton and Audrey, he calls out: "Silent upon a peak in Darien!" This is the last line from John Keats's 1816 sonnet "On First Looking into Chapman's Homer". The literary reference not only demonstrates the character's knowledge of classic texts, but the poem's reference to the Pacific Ocean matches Mayhew's announcement that he will "jus' walk on down to the Pacific, and from there I'll ... improvise".[68]

The title of Barton's play, Bare Ruined Choirs, comes from line four of Sonnet 73 by William Shakespeare. The poem's focus on aging and death connects to the movie's exploration of artistic difficulty.[69] Other academic allusions are presented elsewhere, often with extreme subtlety. For example, a brief shot of the title page in a Mayhew novel indicates the publishing house of "Swain and Pappas". This is likely a reference to Marshall Swain and George Pappas, philosophers whose work focuses on themes explored in the movie, including the limitations of knowledge and nature of being.[70] One critic notes that Barton's fixation on the stain across the ceiling of his hotel room matches the protagonist's behavior in the short story "The Enduring Chill" by author Flannery O'Connor.[71]

Critics have suggested that the movie indirectly references the work of writers Dante Alighieri (through the use of Divine Comedy imagery) and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (through the presence of Faustian bargains).[72] Confounding bureaucratic structures and irrational characters, like those in the novels of Franz Kafka, appear in the film, but the Coens insist the connection was not intended. "I have not read him since college," admitted Joel in 1991, "when I devoured works like The Metamorphosis. Others have mentioned The Castle and "In the Penal Colony", but I've never read them."[73]

Clifford Odets[edit]

The character of Barton Fink is based loosely on Clifford Odets, a playwright from New York who in the 1930s joined the Group Theatre, a gathering of dramatists which included Harold Clurman, Cheryl Crawford, and Lee Strasberg. Their work emphasized social issues, and employed Stanislavski's system of acting to recreate human experience as truthfully as possible. Several of Odets' plays were successfully performed on Broadway, including Awake and Sing! and Waiting for Lefty (both in 1935). When public tastes turned away from politically engaged theatre and toward the familial realism of Eugene O'Neill, Odets had difficulty producing successful work, so he moved to Hollywood and spent twenty years writing film scripts.[74]

The resemblance of Clifford Odets to actor John Turturro is "striking", according to critic R. Barton Palmer.[75]

The Coens wrote with Odets in mind; they imagined Barton Fink as "a serious dramatist, honest, politically engaged, and rather naive".[76] As Ethan said in 1991: "It seemed natural that he comes from Group Theater and the decade of the thirties."[76] Like Odets, Barton believes that the theatre should celebrate the trials and triumphs of everyday people; like Barton, Odets was highly egotistical.[77] In the movie, a review of Barton's play Bare Ruined Choirs indicates that his characters face a "brute struggle for existence ... in the most squalid corners". This wording is similar to the comment of biographer Gerald Weales that Odets' characters "struggle for life amidst petty conditions".[70] Lines of dialogue from Barton's work are reminiscent of Odets' play Awake and Sing!. For example, one character declares: "I'm awake now, awake for the first time." Another says: "Take that ruined choir. Make it sing."[78]

However, many important differences exist between the two men. Joel Coen said: "Both writers wrote the same kind of plays with proletarian heroes, but their personalities were quite different. Odets was much more of an extrovert; in fact he was quite sociable even in Hollywood, and this is not the case with Barton Fink!"[76] Although he was frustrated by his declining popularity in New York, Odets was successful during his time in Hollywood. Several of his later plays were adapted – by him and others – into movies. One of these, The Big Knife, matches Barton's life much more than Odets'. In it, an actor becomes overwhelmed by the greed of a movie studio which hires him, and eventually commits suicide.[79] Another similarity to Odets' work is Audrey's death, which mirrors a scene in Deadline at Dawn, a 1946 film noir written by Odets. In that film, a character wakes to find that the woman he bedded the night before has been inexplicably murdered.[80]

Odets chronicled his difficult transition from Broadway to Hollywood in his diary, published in 1988 as The Time Is Ripe: The 1940 Journal of Clifford Odets. The diary explored Odets' philosophical deliberations about writing and romance. He often invited women into his apartment, and describes many of his affairs in the diary. These experiences, like the extended speeches about writing, are echoed in Barton Fink when Audrey visits and seduces Barton at the Hotel Earle.[81] Turturro was the only member of the production who read Odets' Journal, however, and the Coen brothers urge audiences to "take account of the difference between the character and the man".[76]

William Faulkner[edit]

Actor John Mahoney was selected for the part of W.P. Mayhew "because of his resemblance to William Faulkner" (pictured).[76]

Some similarities exist between the character of W.P. Mayhew and novelist William Faulkner. Like Mayhew, Faulkner became known as a preeminent writer of Southern literature, and later worked in the movie business. Like Faulkner, Mayhew is a heavy drinker and speaks contemptuously about Hollywood.[76] Faulkner's name appeared in the Hollywood 1940s history book City of Nets, which the Coens read while creating Barton Fink. Ethan explained in 1998: "I read this story in passing that Faulkner was assigned to write a wrestling picture.... That was part of what got us going on the whole Barton Fink thing."[82] Faulkner worked on a 1932 wrestling film called Flesh, which starred Wallace Beery, the actor for whom Barton is writing.[83] The focus on wrestling was fortuitous for the Coens, as they participated in the sport in high school.[82]

However, the Coens disavow a significant connection between Faulkner and Mayhew, calling the similarities "superficial".[76] "As far as the details of the character are concerned," Ethan said in 1991, "Mayhew is very different from Faulkner, whose experiences in Hollywood were not the same at all."[76] Unlike Mayhew's inability to write due to drink and personal problems, Faulkner continued to pen novels after working in the movie business, winning several awards for fiction completed during and after his time in Hollywood.[84]

Jack Lipnick[edit]

Lerner's Academy Award-nominated character of studio mogul Jack Lipnick is a composite of several Hollywood producers, including Harry Cohn, Louis B. Mayer, and Jack Warner – three of the most powerful men in the film industry at the time in which Barton Fink is set.[85] Like Mayer, Lipnick is originally from the Belarusian capital city Minsk. When World War II broke out, Warner pressed for a position in the military and ordered his wardrobe department to create a military uniform for him; Lipnick does the same in his final scene. Warner once referred to writers as "schmucks with Underwoods", leading to Barton's use in the film of an Underwood typewriter.[86]

At the same time, the Coens stress that the labyrinth of deception and difficulty Barton endures is not based on their own experience. Although Joel has said that artists tend to "meet up with Philistines", he added: "Barton Fink is quite far from our own experience. Our professional life in Hollywood has been especially easy, and this is no doubt extraordinary and unfair."[20] Ethan has suggested that Lipnick – like the men on which he is based – is in some ways a product of his time. "I don't know that that kind of character exists anymore. Hollywood is a little more bland and corporate than that now."[87]

Cinema[edit]

The Coens have acknowledged several cinematic inspirations for Barton Fink. Chief among these are three movies by Polish-French filmmaker Roman Polanski: Repulsion (1965), Cul-de-Sac (1966), and The Tenant (1976). These movies employ a mood of psychological uncertainty, coupled with eerie environments that compound the mental instability of the characters. Barton's isolation in his room at the Hotel Earle is frequently compared to that of Trelkovsky in his apartment in The Tenant.[88] Ethan said regarding the genre of Barton Fink: "[I]t is kind of a Polanski movie. It is closer to that than anything else."[61] By coincidence, Polanski was the head of the jury at the Cannes Film Festival in 1991, where Barton Fink first premiered. This created an awkward situation. "Obviously," Joel Coen said later, "we have been influenced by his films, but at this time we were very hesitant to speak to him about it because we did not want to give the impression we were sucking up."[2]

Other works cited as influences for Barton Fink include Stanley Kubrick's 1980 film The Shining and the 1941 comedy Sullivan's Travels, written and directed by Preston Sturges.[89] Set in an empty hotel, Kubrick's movie concerns a writer unable to proceed with his latest work. Although the Coens approve of comparisons to The Shining, Joel suggests that Kubrick's film "belongs in a more global sense to the horror film genre".[2] Sullivan's Travels, released the year in which Barton Fink is set, follows successful director John Sullivan, who decides to create a movie of deep social import – not unlike Barton's desire to create entertainment for "the common man". Sullivan eventually decides that comedic entertainment is a key role for filmmakers, similar to Jack Lipnick's assertion at the end of Barton Fink that "the audience wants to see action, adventure".[90]

Additional allusions to films and film history abound in Barton Fink. At one point a character discusses "Victor Soderberg"; the name is a reference to Victor Sjöström, a Swedish director who worked in Hollywood under the name Victor Seastrom.[91] Charlie's line about how his troubles "don't amount to a hill of beans" is a probable homage to the 1942 film Casablanca. Another similarity is that of Barton Fink's beach scene to the final moment in 1960's La Dolce Vita, wherein a young woman's final line of dialogue is obliterated by the noise of the ocean.[92] The unsettling emptiness of the Hotel Earle has also been compared to the living spaces in Key Largo (1948) and Sunset Boulevard (1950).[61]

Themes[edit]

Two of the film's central themes – the culture of entertainment production and the writing process – are intertwined and relate specifically to the self-referential nature of the work (as well as the work within the work). It is a movie about a man who writes a movie based on a play, and at the centre of Barton's entire opus is Barton himself. The dialogue in his play Bare Ruined Choirs (also the first lines of the film, some of which are repeated at the end of the film as lines in Barton's screenplay The Burlyman) give us a glimpse into Barton's self-descriptive art. The mother in the play is named "Lil", which is later revealed to be the name of Barton's own mother. In the play, "The Kid" (a representation of Barton himself) refers to his home "six flights up" – the same floor where Barton resides at the Hotel Earle. Moreover, the characters' writing processes in Barton Fink reflect important differences between the culture of entertainment production in New York's Broadway district and Hollywood.[93]

Broadway and Hollywood[edit]

Although Barton speaks frequently about his desire to help create "a new, living theater, of and about and for the common man," he does not recognize that such a theater has already been created: the movies. In fact, he disdains this authentically popular form.[94] On the other hand, the world of Broadway theatre in Barton Fink is a place of high culture, where the creator believes most fully that his work embodies his own values. Although he pretends to disdain his own success, Barton believes he has achieved a great victory with Bare Ruined Choirs. He seeks praise; when his agent Garland asks if he's seen the glowing review in the Herald, Barton says "no", even though his producer had just read it to him. Barton feels close to the theatre, confident that it can help him create work that honors "the common man". The men and women who funded the production – "those people", as Barton calls them – demonstrate that Broadway is just as concerned with profit as Hollywood; but its intimacy and smaller scale allow the author to feel that his work has real value.[95]

In the film, Hollywood demonstrates many forms of what author Nancy Lynn Schwartz describes as "forms of economic and psychological manipulation used to retain absolute control".[96]

Barton does not believe Hollywood offers the same opportunity. In the film, Los Angeles is a world of false fronts and phony people. This is evident in an early line of the screenplay (filmed, but not included in the theatrical release[97]); while informing Barton of Capitol Pictures' offer, his agent tells him: "I'm only asking that your decision be informed by a little realism – if I can use that word and Hollywood in the same breath."[98] Later, as Barton tries to explain why he's staying at the Earle, studio head Jack Lipnick finishes his sentence, recognizing that Barton wants a place that is "less Hollywood". The assumption is that Hollywood is fake and the Earle is genuine. Producer Ben Geisler takes Barton to lunch at a restaurant featuring a mural of the "New York Cafe", a sign of Hollywood's effort to replicate the authenticity of the east coast.[26] Lipnick's initial overwhelming exuberance is also a façade. Although he begins by telling Barton that "the writer is king here at Capitol Pictures", in the penultimate scene he insists: "If your opinion mattered, then I guess I'd resign and let you run the studio. It doesn't, and you won't, and the lunatics are not going to run this particular asylum."[99]

Deception in Barton Fink is emblematic of Hollywood's focus on low culture, its relentless desire to efficiently produce formulaic entertainment for the sole purpose of economic gain. Capitol Pictures assigns Barton to write a wrestling picture with superstar Wallace Beery in the leading role. Although Lipnick declares otherwise, Geisler assures Barton that "it's just a B picture". Audrey tries to help the struggling writer by telling him: "Look, it's really just a formula. You don't have to type your soul into it."[100] This formula is made clear by Lipnick, who asks Barton in their first meeting whether the main character should have a love interest or take care of an orphaned child. Barton shows his iconoclasm by answering: "Both, maybe?"[101] In the end, his inability to conform to the studio's norms destroys Barton. A similar depiction of Hollywood appears in Nathanael West's 1939 novel The Day of the Locust, which many critics see as an important precursor to Barton Fink.[102] Set in a run-down apartment complex, the book describes a painter reduced to work decorating movie sets. It portrays Hollywood as crass and exploitative, devouring talented individuals in its neverending quest for profit. In both West's novel and Barton Fink, protagonists suffer under the oppressive industrial machine of the movie studio.[103]

Writing[edit]

The film contains further self-referential material, as a film about a writer having difficulty writing (written by the Coen brothers while they were having difficulty writing another project). Barton is trapped between his own desire to create meaningful art and the need of Capitol Pictures to use its standard conventions to earn profits.[101] Audrey's advice about following the formula would save Barton if he heeded it. He does not, but when he puts the mysterious package on his writing desk, she may be helping him posthumously, in other ways.[104] The movie itself toys with standard screenplay formulas. As with Mayhew's scripts, Barton Fink contains a "good wrestler" (Barton, it seems) and a "bad wrestler" (Charlie) who "confront" each other at the end. But in typical Coen fashion, the lines of good and evil are blurred, and the supposed hero in fact reveals himself to be deaf to the pleadings of his "common man" neighbor. By blurring the lines between reality and surreal experience, the film subverts the "simple morality tales" and "road maps" offered to Barton as easy paths for the writer to follow.[105]

However, the filmmakers point out that Barton Fink is not meant to represent the Coens themselves. "Our life in Hollywood has been particularly easy", they once said. "The film isn't a personal comment."[106] Still, universal themes of the creative process are explored throughout the movie. During the picnic scene, for example, Mayhew asks Barton: "Ain't writin' peace?" Barton pauses, then says: "No, I've always found that writing comes from a great inner pain."[107] Such exchanges led critic William Rodney Allen to call Barton Fink "an autobiography of the life of the Coens' minds, not of literal fact".[108]

Fascism[edit]

Several of the film's elements, including the setting at the start of World War II, have led some critics to highlight parallels to the rise of fascism at the time. For example, the detectives who visit Barton at the Hotel Earle are named "Mastrionatti" and "Deutsch"[109] – Italian and German names, evocative of the regimes of Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler. Their contempt for Barton is clear: "Fink. That's a Jewish name, isn't it? ... I didn't think this dump was restricted."[110] Later, just before killing his last victim, Charlie says "Heil Hitler".[111] Jack Lipnick hails originally from the Belarusian capital city Minsk, which was occupied from 1941 by the Nazis, following Operation Barbarossa.[112]

"[I]t's not forcing the issue to suggest that the Holocaust hovers over Barton Fink", writes biographer Ronald Bergan.[48] Others see a more specific message in the film, particularly Barton's obliviousness to Charlie's homicidal tendencies. Critic Roger Ebert wrote in his 1991 review that the Coens intended to create an allegory for the rise of Nazism. "They paint Fink as an ineffectual and impotent left-wing intellectual, who sells out while telling himself he is doing the right thing, who thinks he understands the 'common man' but does not understand that, for many common men, fascism had a seductive appeal." However, he goes on to say: "It would be a mistake to insist too much on this aspect of the movie...."[113]

Other critics are more demanding. M. Keith Booker writes:

Fink's failure to "listen" seems intended to tell us that many leftist intellectuals like him were too busy pursuing their own selfish interests to effectively oppose the rise of fascism, a point that is historically entirely inaccurate ... That the Coens would choose to level a charge of irresponsibility against the only group in America that actively sought to oppose the rise of fascism is itself highly irresponsible and shows a complete ignorance of (or perhaps lack of interest in) historical reality. Such ignorance and apathy, of course, are typical of postmodern film....[43]

For their part, the Coens deny any intention to present an allegorical message. They chose the detectives' names deliberately, but "we just wanted them to be representative of the Axis world powers at the time. It just seemed kind of amusing. It's a tease. All that stuff with Charlie – the "Heil Hitler!" business – sure, it's all there, but it's kind of a tease."[56] In 2001 Joel responded to a question about critics who provide extended comprehensive analysis: "That's how they've been trained to watch movies. In Barton Fink, we may have encouraged it – like teasing animals at the zoo. The movie is intentionally ambiguous in ways they may not be used to seeing."[114]

Slavery[edit]

Although subdued in dialogue and imagery, the theme of slavery appears several times in the movie. Mayhew's crooning of the spiritual tune "Old Black Joe" depicts him as enslaved to the movie studio, not unlike the song's narrator who pines for "my friends from the cotton fields away".[115] One brief shot of the door to Mayhew's workspace shows the title of the movie he is supposedly writing: Slave Ship. This is a reference to a 1937 movie written by Mayhew's inspiration William Faulkner and starring Wallace Beery, for whom Barton is composing a script in the movie.[115]

The symbol of the slave ship is furthered by specific set designs, including the round window in Ben Geisler's office which resembles a porthole, as well as the walkway leading to Mayhew's bungalow, which resembles the boarding ramp of a watercraft.[115] Several lines of dialogue make clear by the film's end that Barton has become a slave to the studio: "[T]he contents of your head," Lipnick's assistant tells him, "are the property of Capitol Pictures".[116] After Barton turns in his script, Lipnick delivers an even more brutal punishment: "Anything you write will be the property of Capitol Pictures. And Capitol Pictures will not produce anything you write."[117] This contempt and control is representative of the opinions expressed by many writers in Hollywood at the time.[115][118] As Arthur Miller said in his review of Barton Fink: "The only thing about Hollywood that I am sure of is that its mastication of writers can never be too wildly exaggerated."[119]

"The Common Man"[edit]

During the first third of the film, Barton speaks constantly of his desire to lionise "the common man" in his work. In one speech he declares: "The hopes and dreams of the common man are as noble as those of any king. It's the stuff of life – why shouldn't it be the stuff of theater? Goddamnit, why should that be a hard pill to swallow? Don't call it new theater, Charlie; call it real theater. Call it our theater."[120] Yet, despite his rhetoric, Barton is totally unable (or unwilling) to appreciate the humanity of the "common man" living next door to him.[120] Later in the film, Charlie explains that he has brought various horrors upon him because "you DON'T LISTEN!"[121] In his first conversation with Charlie, Barton constantly interrupts Charlie just as he is saying "I could tell you some stories-", demonstrating that despite his fine words he really isn't interested in Charlie's experiences; in another scene, Barton symbolically demonstrates his deafness to the world by stuffing his ears with cotton to block the sound of his ringing telephone.[122]

Barton's position as screenwriter is of particular consequence to his relationship with "the common man". By refusing to listen to his neighbor, Barton cannot validate Charlie's existence in his writing – with disastrous results. Not only is Charlie stuck in a job which demeans him, but he cannot (at least in Barton's case) have his story told.[123] More centrally, the film traces the evolution of Barton's understanding of "the common man": At first he is an abstraction to be lauded from a vague distance. Then he becomes a complex individual with fears and desires. Finally he shows himself to be a powerful individual in his own right, capable of extreme forms of destruction and therefore feared and/or respected.[124]

The complexity of "the common man" is also explored through the oft-mentioned "life of the mind". While expounding on his duty as a writer, Barton drones: "I gotta tell you, the life of the mind ... There's no road map for that territory ... and exploring it can be painful. The kind of pain most people don't know anything about."[125] Barton assumes that he is privy to thoughtful creative considerations while Charlie is not. This delusion shares the film's climax, as Charlie runs through the hallway of the Earle, shooting the detectives with a shotgun and screaming: "LOOK UPON ME! I'LL SHOW YOU THE LIFE OF THE MIND!!"[126] Charlie's "life of the mind" is no less complex than Barton's; in fact, some critics consider it more so.[127]

Charlie's understanding of the world is depicted as omniscient, as when he asks Barton about "the two lovebirds next door", despite the fact that they are several doors away. When Barton asks how he knows about them, Charlie responds: "Seems like I hear everything that goes on in this dump. Pipes or somethin'."[128] His total awareness of the events at the Earle demonstrate the kind of understanding needed to show real empathy, as described by Audrey. This theme returns when Charlie explains in his final scene: "Most guys I just feel sorry for. Yeah. It tears me up inside, to think about what they're going through. How trapped they are. I understand it. I feel for 'em. So I try to help them out."[129][130]

Religion[edit]

Themes of religious salvation and allusions to Biblical texts appear only briefly in Barton Fink, but their presence pervades the story. While Barton is experiencing his most desperate moment of confusion and despair, he opens the drawer of his desk and finds a Gideon's Holy Bible. He opens it "randomly" to Chapter 2 in the Book of Daniel, and reads from it: "And the king, Nebuchadnezzar, answered and said to the Chaldeans, I recall not my dream; if ye will not make known unto me my dream, and its interpretation, ye shall be cut in pieces, and of your tents shall be made a dunghill."[131] This passage reflects Barton's inability to make sense of his own experiences (wherein Audrey has been "cut in pieces"), as well as the "hopes and dreams" of "the common man".[70] Nebuchadnezzar is also the title of a novel that Mayhew gives to Barton as a "little entertainment" to "divert you in your sojourn among the Philistines".[132]

Mayhew alludes to "the story of Solomon's mammy", a reference to Bathsheba, who gave birth to Solomon after her lover David had her husband Uriah killed. Although Audrey cuts Mayhew off by praising his book (which Audrey herself may have written), the reference foreshadows the love triangle which evolves among the three characters of Barton Fink. Rowell points out that Mayhew is murdered (presumably by Charlie) soon after Barton and Audrey have sex.[133] Another Biblical reference comes when Barton flips to the front of the Bible in his desk drawer, and sees his own words transposed into the Book of Genesis. This is seen as a representation of his hubris as self-conceived omnipotent master of creation, or alternatively as a playful juxtaposition demonstrating Barton's hallucinatory state of mind.[133]

Reception[edit]

Barton Fink premiered in May 1991 at the Cannes Film Festival. Beating competition which included Jacques Rivette's La Belle Noiseuse, Spike Lee's Jungle Fever and David Mamet'