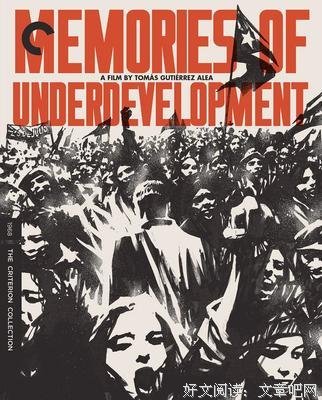

《低度开发的回忆》的影评大全

《低度开发的回忆》是一部由托马斯·古铁雷兹·阿莱执导,塞吉欧·柯瑞里 / 黛西·加纳多斯 / Eslinda Núñez主演的一部剧情类型的电影,特精心从网络上整理的一些观众的影评,希望对大家能有帮助。

《低度开发的回忆》精选点评:

●一个资产阶级作家没有随家人撤离,而是满怀喜悦要目睹革命后的古巴现状。他流连于哈瓦那的街头,沉思并观望着这个国家的变化,然而他也不自觉地因为自己的好色风流而陷入道德危机之中。

●松散叙事架构中穿插政治新闻纪录影像,主角在片中作为无所事事只会读书恋爱的资产阶级是一个被架空的概念,他既是作者用来见证古巴政治局势以及传达政治观点的工具,同时也象征着作为本片主要批判对象的古巴资产阶级,作者镜头底下的古巴资产阶级是一个迷失的与社会脱节的对政治时局无动于衷的冷漠群体

●2016-06-21 古巴电影讲座上观看;【BAMPFA】2018.1.18.7pm 4K修复版。欠发达地区中产阶级男性的欲望/情感状态和美苏博弈间的革命后的国家政治状态,形成了奇妙的对位关系。这种游离、惶惑,欲望奔涌却无法填充,既不想去彼岸(北美)也无法成为“人民”。近乎戈达尔本人,当然是古巴版的。

●20/7/19

●La liberté formelle digne d'1empreinte de la nouvelle vague embrase ce récit intime existentiel d'1 bobo pris dans le tourbillon politico-social de son pays au tournant historique.La superposition des mémoires individuelle et collective donne lieu à 1 chef d'œuvre abosu

●加点新浪潮,古巴使馆DVD

●20200115周三22:30 低度开发的阴郁

●革命、不革命、反革命,以及中间的混沌地带. 知识分子的苦闷大抵相似:思虑深重而行动无能,渴望简单,又希求这简单变得复杂;影片的剪辑模式将政治与情欲一道构建为无处不在而无可逃避之物,一种作为入侵的回忆――但与此同时二者的联系又是脆弱无力的:这客观存在又无能建立的联系,便是"低度开发"的真意所在.正因本片既揭示二者的耦合亦指明了彼此关联的模糊难言之处,它得以与《广岛之恋》和《感官世界》等作品一道,归入政治电影的最高形态.

●文化在一个低度开发的国家 是阵痛和费用昂贵的手术 六月腐烂敏感点..

●感觉书会更精彩

《低度开发的回忆》影评(一):别人打了鸡血,我却很衰!

阿莱雅作为当时一流的电影导演拍出这样美又毫无任何宣传价值的作品,居然被通过了,这真是一大谜题了。

原来在1968年当时的知识分子界,所有人都处于怀疑的情况下,他们太喜欢这样只有不断的问问题,而且有单纯美感的娱乐作品了。仅仅是在四处紧张的革命氛围下,能娱乐一下也是好的,他们太惜才了。

这种思维状态,和电影中描写的1962年的小作家是同构的。革命爆发以后,资产阶级情调的女神橱窗里被换上了卡斯特罗的画像,持枪的女青年和肆意舞蹈的黑人男性,走街串巷时总是能碰到。这些即兴拍摄的素材,和整体画面竟毫不突兀。

很多评论都称这个小作家是花花公子,殊不知他就是导演和原著作家自己的写照。不就是一个喜欢和女子厮混的贾宝玉吗?10岁上教会学校,13岁到妓院破了雏,以后每周都去。和一个毫不体贴自私任性的劳拉结婚以后,他发现自己的天赋,幻想着过一种作家的生活。这时他又认识了年轻丰满的汉娜,他说这是上帝给他最好的礼物。随着革命的到来,一切都被打断了,历史起于日常生活断裂之处,他的家人都去了迈阿密。

这时候他能做的是什么?除了上街遛弯儿,除了在家幻想和女佣乱搞,在河里为她进行洗礼。他靠几套公寓的出租费用来生活,后来也被没收了。所以电影的主题就变成了他和17岁的少女伊莲娜拍拖的,后来被控诉而获胜的故事。

没有什么开始也没有什么结束,正像片名所说的低度开发的回忆,发生的这些事情,似未铸成记忆。当然另外一方面也提示他鲜明的阶级性,他和平民阶级无法建立什么联系,非常荒诞的生活。

女性的电影有阴道独白,而这是一篇极佳的古巴革命独白。捕捉到了气息。

跟我们想象中的一味打鸡血的古巴革命不一样。

《低度开发的回忆》影评(二):【说吧,记忆……】

那一年,赛尔乔38岁,他游荡在街上,坐在街边的照相摊位上拍了一张标准照,平庸,落魄,全然没有从前的风采,呆滞的眼神不知望向哪里。

画外,有一个声音:38岁,老了,只觉得蠢了,生硬了,就像坏掉的水果,就像废物。或许是身处热带的关系,所有的东西都不持久……

男人席地而坐,身边都散乱的抽屉和相册,他在翻看旧日的照片——

心底,有一个声音:我已经老了,15岁时我是天才,25岁我就有了自己的商店,然后,罗拉,我的妻子,像是装饰的植物……

他想念父母,除了“此时”和父母的旧照片,另外有个细节,就是母亲给他的信封里总是有口香糖和老式的刮脸刀片,尽管他平时只用电动的剃须刀。他从信箱取出信,对着楼外的阳光照了一下,不用拆开他也知道是什么,他笑了……

他席地而坐,翻看旧日的照片。这个场景如此熟悉,所有的怀旧者都有这样的动作,拿起一张却也不舍得放下,一张一张聚在手里。动作缓慢,也有些迟疑,怕打搅了什么,也怕更深地浸入。

而后,当他发现了更为清澈的回忆,松开手,他看见纷纭的时间正在飘落,他看见遍地的日子仍在生长,他看见旧年的影子长久伫立,长得像永远了。

《说吧,记忆》第二章开头有段话:当我远溯往昔,回忆我自己,我一向听从温和的幻想,有的属于听觉,别的则属于视觉……就在入睡之前,我常常觉察到一种单向的对话在我头脑中某个附属部位继续着,完全独立于思想的实际倾向。那是中性的,超然的,匿名的声音……

黑白照片上的亲人和朋友在向他微笑,他听见了那种声音。

这是一个38岁开始回忆、开始总结的男人。

这一幕,如此心动。

夜里,公园的舞会早已散场,回想起那段纯正的哈瓦那的歌谣,起舞的人群匆匆旋转,看不清彼此的神情。

这部影片里几乎没有巴西音乐,都是很老的爵士配上很闷的鼓声。

赛尔乔走在街上,街灯恍惚,两边是整装待发的军队和坦克,他左右张望,他在找寻什么?

这岛是个陷阱——他看到了这个陷阱正在吞噬这个城市,这个国家,还有深陷其间的人民。

他说:我们很微小,很贫穷,尊严很珍贵。

孤岛之上,人们在等待必然的结局,他留在这里,是一个错误吗?若是和父母和妻子一同离开又将怎样呢?

虽然左顾右盼,但他并没有悔意。

他回家,走到阳台上的望远镜跟前,他不再看脚下的灯火,把镜头转向夜空,看月亮之上正吹过的云翳。

转天,又一个黎明,是空镜——笛声低缓,苍凉,时而几个清亮的滑音。鼓声阵阵,暗哑,沉闷,似是惘惘中的警诫。

前景是男人放在阳台上的望远镜,空落落的一览无遗,它似乎看清了一切发生的,还有将要发生的,是先知的目光。

镜头沿着望远镜漫漫漾开,有逡巡和抚摸的意味,街上排列整齐的装甲车正在挺进。

时而,有一阵清风,从船上吹来。

好电影,当要好好看。

电影接连看了两遍,即使两天之后我也不能简单而直接地说:感动。我觉得,这太潦草了。

就像在这部电影里,无法说:戏。《低度开发的记忆》尽管隔了年代,但是仍真实到触手可及。

看电影的时候,我常常忘记了这是1968年的、隔了整整半个世纪的作品,导演的叙述笔调,摄影的选取角度,剪辑的手法均为上乘之作,相比近年的诸多电影,尤显高超。

甚至包括电影的海报,也极为精准地抓住作家的一刹那:他手扶望远镜,但是和镜头还有一点距离,脸上的表情似乎无限渴望,似乎已入梦呓……画外,或窗外就是他渴望融入的社会变革,然而却总有一段观望的距离,让他无法纵身。

片头他用望远镜一遍遍看半城的街道,和街上的人们,到了片尾他看夜空,看残缺的月亮。

而最后,是空镜,时代径直前进,你不能阻止任何。

剧中的男演员具有非凡魅力,举手投足都恰如他的身份,这些细节纷纷可以指正,他是有来历的,是电影中的、深处变革中的资产阶级作家。

影片里有许多他的背影,并从他的背影去看这个城市,他的凝望,他的眼神里都有一种人物赋予他的、或者他赋予人物的光彩,无分你我,是两股力交织在一起的合力。

惟有在这种坚定的、有其质地的凝望中,才能将一个时代的记忆,铺展开来。

低度开发的记忆——我不知道这篇文字该叫什么,似乎怎样的语句附着其后都是多余。想了很久,想借用纳博科夫的自传《说吧,记忆》为题,以其清浅为引线,如喃喃的召唤,如谆谆诱导的咒语:

说吧,记忆……

动笔前,没有给自己规定字数,也没有提纲,是3000字还是6000字全无所谓。写到这儿,差不多完全遵循影片中的叙事脉络,我不舍得绕开影片自然而精心设计的结构。只不过把当年的新闻资料聚攒在一处,权当背景。

说实话,我只能说出电影中的一半。

我也可以承认这些笔记并不是导演致力讲述的,而是局部的流露和展现。他的主题当在故事背后。当然,这不仅是一个爱情故事,甚至我怀疑他们之间是否有过相对稳定的爱情。

然而,我不在乎这是主题还是隐线,是我关注的一个人在一段时间的衍进,和内心的些许变迁。

在这一半的电影里,我感受到导演赋予电影的力量,尽管其中的人物有许多无奈和迷茫。

这样一部电影,这样一位导演,他在影片中所灌输的绝不仅仅是化为无声的激情,而是让你在看完电影之后,让长时间留存心中的、他用胶片构筑的时空之中,久久地,不肯出来——

这四个字,就是无言的感激,就是无尽地深入,就是期待从简洁有力的电影语言中获得更多的力量所在。

我说,不论从任何意义或角度,这部电影都是穿越了时空的经典。

想起近两年看的还有盖•马丁(Guy Maddin)的《世界上最悲伤的音乐》(The Saddest Music in the World/2006)和《我的温尼伯湖》(My Winnipeg/2008),还有特伦斯•戴维斯(Terence Davies)的《彼时,彼城》(Of Time And The City/2008)似有某种鲜明的传承或延伸、或递进关系。

同是家族、城市和国家的变迁,都是从一种单纯的个人视角娓娓道来——回忆,偕同倒叙,大量的纪录片镜头穿插——叙述中有陡升的波澜,也有暗涌的情愫,无法抚慰的记忆最后归于一派平静的低语。

低度开发的记忆之外,是大面积的原始累计,像晴空下的麦浪,一茬一茬地,前面收割后面还在生长。

时间,并非我们想象中一定具有决然的公正,时间自有厚薄之别,回忆也有冷暖之分。

深锁的记忆,和悠长的回忆,共同创造出一片凝住的时空,既来自过去,也关乎未来——那里,有生命的记忆。

那一定是在存在于这个世界上的第四维度:A Place in the World……

低语,是内心的声音。

记忆的坦白和迷藏,均在斑驳的影像之中了。

很浅的黑白,杂糅成干净的灰,柔和的光从四面涌来,并不耀眼。那时候,时间祥和而雍容,记忆也是。

想起电影中的一幕,或世界上的某个地方:满城狂风大作,他走来,身后是惊涛骇浪,他越走越近,风也越刮越大,把海浪吹成了一片迷蒙的云烟,失了重量,只能在身后飘拂而过。

黑白影像,间或有着细微的、或大片的雪花颗粒翻转腾云,素白色调,一派天光。

说吧,记忆——竟像是一声叹息了。

【低度开发的记忆】

Memorias del subdesarrollo

又名:Memories of Underdevelopment

Inconsolable Memories

Historias del subdesarrollo

导演:托马斯•古蒂尔雷兹•阿莱 Tomas Gutierrez Alea

主演:托马斯•古蒂尔雷兹•阿莱 Tomas Gutierrez Alea

Edmundo Desnoes

ergio Corrieri

语言:西班牙语

制片国家/地区:古巴

上映日期:1968-08-19

1970年捷克卡罗维发利国际电影节评委会奖

1970年捷克卡罗维发利国际电影节影评人费比西奖

1974年全美影评人协会最佳外语片奖

《低度开发的回忆》影评(三):Crisis of the Intellectual in a Post-Revolutionary Society

Memories of the Underdevelopment (Alea, 1967) portrays a good-looking bourgeois man’s self-examined life in post-revolutionary Cuba. Through the character’s affairs and fantasies, the film shows the shortcomings of an apathetic and bitter individual and critiques his bourgeois roots. Yet the Cuban film is also atypically ambivalent in its characterization of bourgeois mentality, since it also to show tensions between an intelligent individual and his overwhelming social reality. Memories places the main character, Sergio in the space of post-revolutionary Cuba, to show the contradictions of a non-partisan intellectual in a highly politicized setting. Political and irrational actions of “the People” override the intellectuals’ critical thinking and theoretical concepts. As Latin American intellectuals, director Tomás Gutiérrez Alea and the author Edmundo Desnoes of the novella, in which the film was based on, identify with Sergio’s dilemmas and “break down the vocabulary of [their] own existence” . A self-reflective and nuanced work, the film avoids cliché by empathizing with its protagonist, Sergio, as well as presenting a critique of his aloofness.

ergio struggles to depart from his bourgeois mentality, but he prides individuality over sociopolitical cohesion in post-revolutionary Cuba. Sergio's diary, presented in a voiceover, exposes personal struggles and contradictions. He tries to escape his “stupid Cuban bourgeois” backgrounds by staying in post-revolutionary Cuba, yet maintains a middle class life style and avoids political activity. He is presented as a hypocrite when he seeks revenge upon those who shaped his bourgeois mentality. Reminiscing over his teenage years, Sergio labels his best friend's father a “freethinker”, only to explain that "he gave [his son] a peso a week for the whorehouse". This acerbic comment does not preclude Sergio from admitting that he also patronized it weekly. Presently, Sergio regards his fellow socialite Pablo as a crass and self-congratulating "asshole", yet Pablo was one of his closest friends who shared his bourgeois mentality. “Pablo is me, everything I don’t want to be,” the bitter and directionless character admits in a detached tone. Yet in the name of protecting individuality, Sergio’s defense mechanism prevents him from partaking social responsibility. Without taking risks to change his situation and remaining conscious of everyone’s shortcomings, Sergio preserves a sick pride and narcissistic dignity that he regards as essential for a conscious individual.

Despite Sergio’s status as a member of the elite and a misfit in the construction of Socialist Cuba, Sergio is not reduced to a caricature. The film adaptation of Desnoe’s first-person novella uses Sergio’s voiceover comments sparingly, allowing more room for the cinematic language and creating a whimsical and humorous character. A contrasting street scene reveals tension between metropolitan consumerism and post-revolutionary Cuba through pure cinematic language. Both Sergio and the audience observe different women on the streets through a series of point-of-view medium close-up shots. Most are dressed in fashion and have chic hairstyles. One of them eats an ice cream. This follows a shot of the main character stopping by a book store. Individual consumerist behaviors are contrasted with the national narrative of Socialism, which is represented by this book store crammed with socialist texts. He later assigns depoliticized explanations for the “underdeveloped” women: they are adapting to a tumultuous time period in an “atmosphere [that] is too soft.” This observation spares the regime as responsible for the tensions, but at the same time questions the purpose and logic of political language during an increasingly politicized society.

As an intellectual and aspiring writer, Sergio’s sensitivity towards language is shown through his sporadic and spontaneous critiques. They are presented through a nonlinear and subjective collage. In the scene where Sergio overlooks the city through a telescope, he comments on wherever the lenses lands on, ranging from people to monuments. The removed Imperialist eagle reminds Sergio of Pablo Picasso’s promised dove replacement and hypocrisy: "It's real easy to be a Communist and millionaire in Paris." Desnoes himself is not spared: Sergio mocks the author as the latter lights a cigar during a discussion panel. “You would be nothing abroad. But here, you have a place. Lack of competition makes you feel important,” Sergio thought in his mind.

While Sergio’s comments are not organized, they are at times extremely political. Unlike the reclusive writer who imagines a fictitious world in order to compensate for life’s dismal realities, Sergio observes and reflects on local events. He remains conscious and open to his contradicting surroundings because he desires to grasp a concrete understanding of his time and place. In one scene, when the vulgar friend Pablo claims to have an apolitical conscience, Sergio ponders upon dialectics of the group and individual in terms of assigning responsibility and guilt. Sergio’s Marxist analysis of the Bay of Pigs incident is accompanied with emotional accusations from the victims and dissociating defenses from the invaders, as the mise-en-scene shows a montage edited from newsreels, contrasting violence and hunger with scenes of industrialization and socializing elites. While the Cuban socialist regime is not specifically targeted in Sergio’s nonlinear comments, it is not spared from philosophical speculations that include all political systems. Rooted in teenage memories, Sergio saw a mutual relationship between justice and power when schools of preaching priests were replaced with indoctrinating Communists. Sergio’s political reflections expose contradictions of a post-revolutionary society, yet he understands that certain shortcomings are not only caused by class strictures, political affiliation or lack of education, but also by universal human flaws.

ergio never wanted to live a life that was motivated by self-interests and egotistical desires like people on either side of the Cold War. Sergio’s political disengagement enables him to criticize and satirize everything. Once he decides for political commitment, he will have a more systematic view of the world, but to Sergio, the ability for free thought is worth more. Sergio shows that the individual, unlike a polity, is not directed by a general guideline. Although he tries to relate to his increasingly politicized surroundings, his efforts fail to establish a coherent understanding. He does not follow any existing tradition or ideology in hope to preserve his sensibility and multitude.

For Sergio’s unrelenting efforts, self-reflective attitude and idiosyncratic philosophy, some Western metropolitan critics perceive Sergio as an “intellectual antihero like the young Mastroianni in a film by Antonioni or Fellini” . Yet the crisis within Sergio is specific to Latin American intellectuals who faced similar tensions during their societies’ post-revolutionary stages. Desgarramiento, which is an ideological rupture with the past, challenges the intellectuals of revolutionary Latin America to redefine their roles. By exploring the intellectual’s role dialectical tensions between language and action in a revolution, Desnoes and other well-known writers participate in a roundtable discussion on “Literature and Underdevelopment” in a self-reflexive Third Cinema moment. Intellectuals explore their global status and how to further the revolutionary efforts through literature. Yet the discussion is dismissed by an American, Jack Gelber, who suggests that a total revolution should not be represented by traditional forms. A revolutionary society is motivated primarily by passion and active commitment, which is challenging for intellectuals accustomed to rational evaluation and dry discussion. Unlike “the People”, intellectuals theorize more often than practice revolution—and they share Sergio’s experiences of loss of individuality and critical thinking in a highly politicized environment.

As Latin Americans, the author and director each have different reasons for choosing a subtle narrative over a propagandistic one: While Alea believes that portraying a trapped bourgeois intellectual would motivate “the People” of Cuba to examine their own contradictions and commit more to the revolution, Desnoes wishes to capture specific aspects of the intellectual’s identity crisis within the revolutionary process. Through Sergio’s nuanced character, Desnoes empathizes with the dispassionate and nonpartisan intellectual and sketches a rough self-portrait. In an issue of Cine Cubano Desnoes says that “there is a struggle between the best products of the bourgeois way of life—education, travel and money—and an authentic revolution” . While Memories critiques Sergio for his bourgeois mentality in post-revolutionary Cuba, it also explores the tensions presented to an observant and nonpartisan intellectual in a polarized environment. The environment pressures the nonpartisan individual to choose between sides, yet either choice contains the risk of losing integrity and individuality.

The contradictions of Sergio’s life in an increasingly politicized setting lead him to destruction. The tragic ending of Memories does not celebrate the demise of a class enemy, but expresses worries for the intellectual as an individual freethinker in post-revolutionary Cuba. While visiting Ernest Hemingway’s Havana house, Sergio consciously compares himself with Hemingway: Both are depressed and escape from their overwhelming social reality. They cage themselves in Cuba, which becomes increasingly polarized and foreign to them. Instead of taking sides, Sergio eventually accepts his alienation and quietly stares into an abyss while collaged images of the world is raucous as ever, “talking about war like it’s a game”. Sergio is exhausted and refuses to think any further, acknowledging the fact that no matter how conscious he understands his situation, nuclear war will annihilate him along with the other “stupid bourgeois” and proletariats. He is a vulnerable individual facing an overwhelming social environment that groups people by political commitment. Despite criticizing the intellectual’s apathy relating it to his bourgeois upbringing, the nuanced film does not celebrate the destruction of Sergio; rather, it mourns the loss of the intellectual’s individuality.

otes

Alea, Tomás, and Edmundo Desnoes. Memories of Underdevelopment. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1990. P19

Cham, Mbye B. Exiles: essays on Caribbean cinema. Trenton, N.J.: Africa World Press, 1992.

Meyerson, Michael. Memories of Underdevelopment: The Revolutionary Films of Cuba. New York: Grossman Publishers, 1973.